Fundus Photography and Fluorescein Angiography of Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy

Home / Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus / Disorders of the Retina and Vitreous

Title: Fundus Photography and Fluorescein Angiography of Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy

Author: Kenneth Price, BS

Photographer: Unknown

Date: 7/29/2016

Image or video:

Keywords/Main Subjects: Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy; FEVR

Secondary CORE Category: Retina and Vitreous / Congenital and Developmental Abnormalities

Diagnosis: Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy

Description of Image: Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy (FEVR) is a rare inherited disorder of retinal blood vessel development which leads to incomplete vascularization of the peripheral retina. Inheritance can be autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, or sporadic. The disease ranges from asymptomatic to severe. If there is sufficient retinal ischemia secondary vascular proliferation can lead to fibrosis, traction, retinal detachment and retinal dysplasia. FEVR needs to be distinguished from ROP due to their similar appearances. The diagnosis of FEVR is made in patients who were born at full term or otherwise have findings inconsistent with ROP and can further be ruled in by genetic testing, specifically testing for FZD4, LRP5, TSPAN12, NDP and FZ mutations among others. Many patients diagnosed with FEVR retain vision of 20/40 or better. Macular ectopia, retinal folds, and retinal detachments are the main causes for visual loss. A fundamental component of diagnosis and treatment is identifying peripheral retinal areas of non-perfusion by performing fluorescein angiography, often under anesthesia due to this disease most commonly presenting in the pediatric age range. Wide-field angiography has become particularly useful in this disease.

This fundus photo and fluorescein angiography photo are from a 4 year old female who was diagnosed with FEVR at an early age after her parents began to notice symptoms of vision loss. On exam, she was found to have an avascular retina peripherally and was followed until she developed neovascularization and associated fibrosis. Fundus photography and fluorescein angiography here show a broad linear macular fold with associated epiretinal membrane and peripheral avascular retina with areas of photocoagulation. She was treated with peripheral photocoagulation, vitrectomies to release vitreoretinal traction, and a scleral buckle for retinal detachment.

References:

Gilmour DF. Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and related retinopathies. Eye (2015) 29, 1–14.

John VJ, McClintic JI, Hess DJ, Berrocal AM. Retinopathy of Prematurity Versus Familial Exudative Vitreoretinopathy: Report on Clinical and Angiographic Findings. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016 Jan;47(1):14-9.

Faculty Approval by: M.E. Hartnett; Griffin Jardine

Disclosure (Financial or other): None

Copyright statement: Copyright 2016. Please see terms of use page for more information.

Stargardt Disease

Home / Retina and Vitreous / Hereditary Retinal and Choroidal Dystrophies

Title: Stargardt disease

Author (s): Jamie Odden, MS4 MPH

Photographer: unknown

Date: 8/16/2016

Image or video:

Figure 2: Fundus autofluorescence demonstrates a hypofluorescent macula corresponding to atrophy and surrounding hyperfluorescent spots corresponding to lipofuscin deposits in the RPE.

Figure 3: OCT. Thinning and disorganization of the inner segment-outer segment (IS-OS) junction of the photoreceptors in the macula (yellow arrow). Accentuated choroidal reflectivity (green bar).

Keywords/Main Subjects: Stargardt Disease; Central macular atrophy; Inherited macular dystrophy

Diagnosis: Stargardt Disease

Description of Image:

Epidemiology: Stargardt disease is the most common inherited macular dystrophy, with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 8,000-10,000 individuals. It is a common cause of central vision loss in individuals under 50 years old, with typical onset between 10-20 years old.

Genetics: The underlying etiology is due to accumulation of lipofuscin in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Most cases are autosomal recessive due to mutations in the ABCA4 gene, which encodes for a transporter protein expressed by rod outer segments. ABCA4 mutations can cause toxins to accumulate in the photoreceptors, leading to formation of lipofuscin. Fewer cases are autosomal dominant due to a mutation in ELOVL4, which encodes a component of the fatty acid elongation system in photoreceptors.

Clinical exam: Classic fundoscopic findings include “beaten bronze” central macular atrophy surrounded by yellow round or pisciform flecks (Figure 1). The condition is referred to as “fundus flavimaculatus” if the discrete yellow flecks are widespread throughout the fundus retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). “Fundus flavimaculatus” is a milder condition rendering better visual function due to less macula involvement.

Diagnosis/testing: Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) and optical coherence tomography (OCT) can confirm diagnosis and help stage the disease. FAF and OCT often detect RPE changes before they are found on clinical fundoscopic exam. Commonly, FAF shows a hypofluorescent macula, corresponding to atrophy, and surrounding hyperfluorescent spots, corresponding to lipofuscin deposits in the RPE (Figure 2).

OCT demonstrates thinning and disorganization of the inner segment-outer segment (IS-OS) junction of the photoreceptors in the macula (Figure 3). Total loss of the IS-OS is possible over time. Choroidal hyper-reflectivity often occurs due to overlying retinal atrophy.

Historically, the “dark choroid sign” on fluorescein angiography (FA) was used to confirm clinical diagnosis, though FA has been largely replaced by FAF and OCT. The sign is present in over 80% of patients. Evidence suggests that the sign is caused by accumulation of lipofuscin throughout the RPE which masks background choroidal fluorescence.

Clinical course: In most cases, central vision loss is slow and progressive. Later-onset disease is associated with a better prognosis. Visual acuity ranges from 20/50 to 20/200, with most individuals maintaining fair acuity in one eye.

Management: Stargardt disease is incurable. No treatments are available to slow progression, though pharmacologic and genetic therapies are under investigation. Individuals should avoid vitamin A supplementation and minimize exposure to bright sunlight. Additionally, low vision therapy should be considered.

Format: image

References:

- North V, Gelman R, Tsang SH. Juvenile-Onset Macular Degeneration and Allied Disorders. Developments in ophthalmology. 2014;53:44-52. doi:10.1159/000357293.

- Liu A, Lin Y, Terry R, Nelson K, Bernstein PS. Role of long-chain and very-long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in macular degenerations and dystrophies. Clin Lipidol. 2011;6(5):593-613.

- Regillo C, ed. Basic and clinical science course (BCSC) 2012-2013: Retina and vitreous section 12. San Francisco, United States: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2012.

Identifier: Moran_CORE_23820

Faculty Approval by: Paul Bernstein, MD PhD; Griffin Jardine, MD

Disclosure (Financial or other): None

Copyright statement: Copyright 2015. Please see terms of use page for more information.

Primary Acquired Melanosis (PAM) with Atypia: Pathology and Clinical Correlations

Home / External Disease and Cornea / Neoplasms of the Conjunctiva and Cornea

Title: Primary Acquired Melanosis (PAM) with Atypia: Pathology and Clinical Correlations

Author (s): Jack Li, BA

Photographer:

- Pathology Photomicrographs: Jack Li

- Clinical Photo: Dr. Amy Lin

Date: 9/12/2016

Image:

Figure A: External photography of the eye in a patient with primary acquired melanosis. Diffuse melanosis of varying degrees of pigmentation noted.

Figure B: The same eye after surgical excision and cryotherapy. The melanotic lesions have been removed.

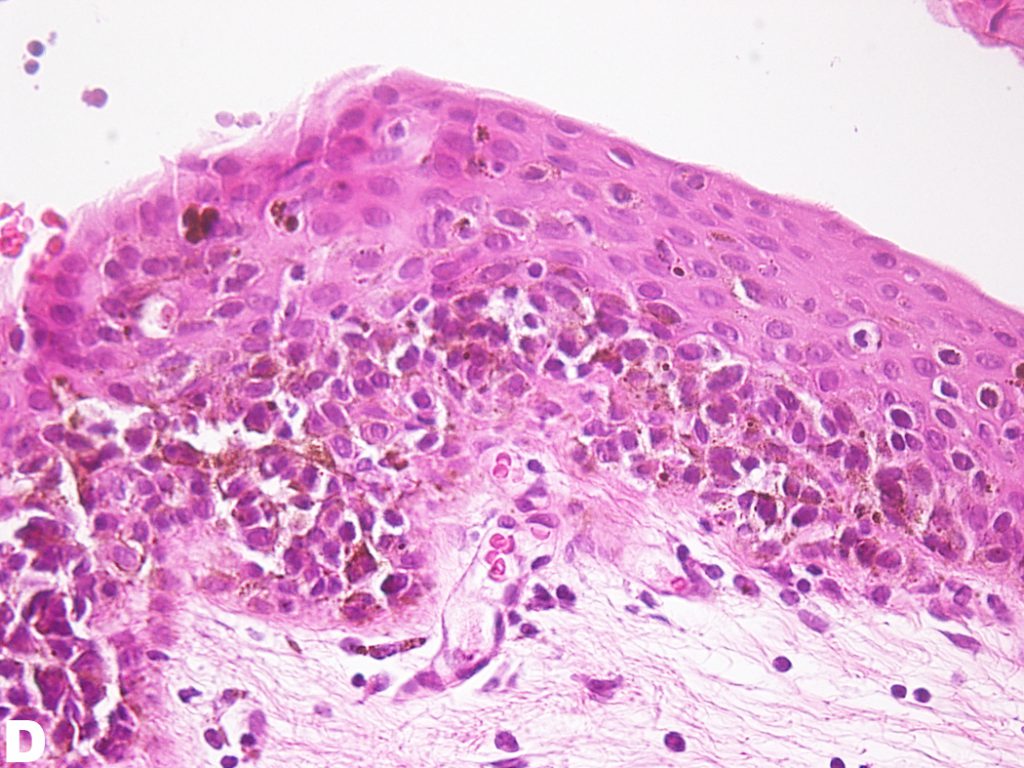

Figure C: Medium magnification H&E stain of the conjunctiva. Stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium is observed. Melanin-laden cells are noted near the basement membrane. Atypical cells are appreciated clustered near the basement membrane.

Figure D: Mid-high magnification of H&E stain of the conjunctiva. Atypical cells can be appreciated mid-way through the epithelium. However, atypical cells have not invaded the entire depth of the epithelium.

Secondary CORE Category: Ophthalmic Pathology / Conjunctiva

Keywords/Main Subjects: Primary Acquired Melanosis, Melanocytic Lesions of Ocular

Diagnosis: Primary Acquired Melanosis with Atypia

Description of Images:

Primary acquired melanosis (PAM) of the conjunctiva is a pigmented lesion of the conjunctiva that is flat, painless and non-cystic. PAM typically occurs unilaterally, is more likely to occur in lightly pigmented individuals and is most likely to present in the 6th decade of life. PAM represents 11% of all conjunctival tumors and 21% of all conjunctival melanocytic lesions1. Figure A is the external photography of a 60-year-old female with approximately 13-year history of PAM of the conjunctiva. Features associated with PAM include unilaterality, waxing and waning of size and pigment over time and a mottled or dusted pigmented appearance. PAM most commonly occurs on the bulbar conjunctiva, limbal conjunctiva and cornea. The typical patient is a Caucasian adult presenting around 60 years of age. PAM is divided histopathologically into PAM with or without atypia. PAM with atypia has a high chance of progression into melanoma while PAM without atypia has little chance of progressing to melanoma2. Biopsy and histopathologic examination allow determination of the presence or absence of atypia. Because PAM with atypia has significant risk of progression into melanoma, a potentially lethal tumor, surgical and medical intervention is warranted. Figure B represents the same patient after excision of the lesion and cryotherapy.

PAM without atypia is defined as pigmentation of the conjunctival epithelium with or without benign melanocytic hyperplasia. PAM with atypia is characterized by the presence of atypical melanocytic hyperplasia. Mild atypia is defined as atypical melanocytes confined to the basal layer of the epithelium; severe atypia is defined as atypical melanocytes that extend into the superficial non-basal portion of the epithelium and may contain epitheloid cells1. Figure C and D are low and medium H&E photomicrographs of the specimen obtained from the patient where pigmentation along the basal layer of the epithelium can be appreciated. One can appreciate the extension of atypical melanocytes mid-way into the epithelium, qualifying this lesion to be PAM with severe atypia.

Atypia is determined by cytological features and growth patterns that are associated with malignant potential. Four types of atypical melanocytes include the small polyhedral cells, epitheloid cells, dendritic cells, and spindle cells. Polyhedral cells contain small, round nuclei with little cytoplasm. Epitheloid cells contain abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Spindle cells are aligned such that the long axis are parallel to the basement membrane. Dendritic cells are large cells with complex branching dendrites found along the basilar layer3.

The mainstay of treatment of PAM with atypia is wide excision of the lesion and cryotherapy of the borders of the lesions. Amniotic graft can be applied to the surgical site to facilitate healing. Topical chemotherapy, most commonly with mitomycin-c, can be used as adjuvant therapy in cases of diffuse lesion, positive surgical margins, large lesions that cannot be completely removed, or in cases of recurrent disease2. Interferon a-2b has shown promise as a medical management. A six-week trial showed that successive application of interferon a-2b resulted in shrinking of PAM4.

References:

- Shields, J. A. et al. Primary acquired melanosis of the conjunctiva: experience with 311 eyes. Trans. Am. Ophthalmol. Soc. 105, 61-71–2 (2007).

- Oellers, P. & Karp, C. L. Management of pigmented conjunctival lesions. Ocul. Surf. 10, 251–263 (2012).

- Folberg, R., McLean, I. & Zimmerman, L. Primary acquired melanosis of the conjunctiva. Hum. Pathol. 16, 129–35 (1985).

- Garip, A. et al. Evaluation of a short-term topical interferon α-2b treatment for histologically proven melanoma and primary acquired melanosis with atypia. Orbit 35, 29–34 (2016).

Faculty Approval by: Amy Lin, MD; Griffin Jardine, MD

Identifier: Moran_CORE_23807

Disclosure (Financial or other): None

Copyright statement: Copyright 2017. Please see terms of use page for more information.

Parry-Romberg Syndrome

Home / Orbit, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System / Periocular Malpositions and Involutional Changes

Title: Parry-Romberg Syndrome Case Report

Author: Rebekah Gensure, PhD, 4th Year Medical Student, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School; Laura Hanson, MD, Neuro-Ophthalmology Fellow, John A. Moran Eye Center; Kathleen Digre, MD, John A. Moran Eye Center

Photographer: James Gilman

Date: July 20, 2015

Moran CORE: Orbits, Eyelids, and Lacrimal System/Periocular Malpositions and Involutional Changes/Involutional Periorbital Changes

Keywords/Main Subjects: Parry-Romberg Syndrome, hemifacial atrophy

Diagnosis/Differential Diagnosis: Parry-Romberg Syndrome, post traumatic fat atrophy, hemifacial microsomia (first and second branchial arch syndrome), Goldenhar’s syndrome

Brief Description of Case:

HPI:

A 27-year-old female patient presented with a long history of facial asymmetry and right tongue atrophy. She was diagnosed with Parry-Romberg syndrome 7 years ago, at the age of 20. At the time of her initial diagnosis at an outside institution, the patient report experiencing significant facial pain and wasted facial appearance that had been present for many years and had gone undiagnosed until that point. Presently, the patient is status-post surgical repair (hemifacial fat grafting) with a satisfactory cosmetic result.

The patient also has a history of migraine headache. At the time of the most recent visit, the patient reported improvement in migraine headaches with no preventative medications currently. Headaches have been less frequent (approximately 1 every 2 weeks) and pain rating no worse than 5/10. She also reports episodic ptosis, which appears to be related to migraine and menstrual cycle.

Other ocular history includes a history of treated amblyopia secondary to accommodative esotropia and is still in spectacle correction.

Exam: OCULAR:

Best corrected visual acuities: 20/20 OD and 20/20 OS.

Pupils: 3mm OU light, 7 mm OU dark; briskly reactive OU with no RAPD EOM: -½ OD on right gaze; Orthotropic at distance; exophoria at near Exophthalmometry: 13 mm OD, 16 mm OS

Color Vision: 10/10 OU Ishihara

Stereo Vision: +Fly, 3/3 animals, 7/9 circles IOP: 16 mm Hg OD & OS.

VF: Full OU

SLE: Anterior segment within normal limits

Fundus: Within normal limits; C/D ratio 0.1 OD, 0.2 OS Refraction: OD +2.50 sphere, +0.75 cylinder at axis 25

OS +1.50 sphere, +1.50 cylinder at axis 130

NEURO: Completely normal neurological examination except for the facial asymmetry.

Discussion:

Hemifacial atrophy, also known as Parry-Romberg syndrome, is characterized by a slow progressive deterioration (atrophy) of the skin and subcutaneous tissue structures on half of the face [1]. As it is described by Parry, Henoch and Romberg in the early 19th century, there is wasting of the subcutaneous fat with or without atrophy of adjacent skin, bone, and cartilage [2- 3]. The condition is typically insidious in onset, and progression is variable. In some cases, atrophy may halt before the entire hemi-face is involved but with residual disability [4]. In mild cases, there may be only minor cosmetic effects without any disability.

Because of the relative rarity of this condition, associated clinical conditions have mostly been identified through case reports. For example, in 1985, Sagild and Alving reported a case associating hemiplegic migraine with hemifacial atrophy [5]. Seizures are also commonly reported to co-occur with hemifacial atrophy, particularly contralateral simple partial or generalized seizures [6]. Additionally, Parry-Romberg syndrome has sometimes been associated with localized scleroderma, although this association remains controversial.

Long-term progression of the condition has not been well documented; however, one interesting case report followed several patients over time, including one patient who was followed for over 43 years [7]. For this particular long-term follow-up patient, progression of facial atrophy appeared to progress until age 15 but then slow or stop until age 23, at which point new onset hyperreflexia of the contralateral lower extremity was noted. Over the years, the facial atrophy remained apparently stable, although his neurological function gradually declined; by age 58, he demonstrated wide-based gait with absent plantar and tendon reflexes, mildly diminished pain and temperature sensation, end-position nystagmus, and difficulty with heel-to-shin and tandem testing.

Treatment options are limited for patients diagnosed with Parry-Romberg hemifacial atrophy. Currently, there are no known therapies that will stop progression of the disease.

Reconstruction has been utilized, with variable results depending on the timing of the intervention. For the best results possible, timing of surgery should be strategized according to when the disease appears to have exhausted its course and facial growth is completed [4].

Images or Video:

Figure 1 a): Right hemifacial atrophy at baseline in patient previously diagnosed with Parry- Romberg syndrome; b): Patient with Parry-Romberg syndrome with history of right hemifacial atrophy, status post fat grafting, with satisfactory cosmetic result. (Photographs courtesy of the patient)

Figure 2: Tongue hemiatrophy in patient with diagnosed Parry-Romberg syndrome. (Photograph by James Gilman)

Figure 3: Right enophthalmos observed in patient with Parry-Romberg syndrome with right hemifacial atrophy. Hertel measurements indicated posterior displacement of 3 mm on the affected side (right) compared to the unaffected (left) side. (Photographs by James Gilman)

Summary of the Case:

The patient is a 27-year-old woman with Parry-Romberg syndrome with hemifacial atrophy, status-post reconstructive surgical repair with a satisfactory cosmetic result. Overall, the patient is quite stable, with no major new changes in facial structure visible on external exam as compared to prior exams. Based on the apparent stability of the disease process and satisfaction of the patient with her appearance, the patient was recommended to return to clinic only for yearly follow-up or sooner as needed.

References:

- Esan T and Olusile Hemifacial Atrophy: A Case Report And Review Of Literature. The Internet Journal of Dental Science. 2003. 1(1).

- Parry Collections from the unpublished medical writings of the late Caleb Hillier Parry, M.D., F.R.S. 1825 London: Underwoods. 478–80.

- Romberg, MH; Henoch, EH (1846). Krankheiten des nervensystems (IV: Trophoneurosen). Klinische ergebnisse (in German). Berlin: Albert Förstner. 75–81.

- NINDS Parry-Romberg Information Page [Internet]. Bethesda: Office of Communications and Public Liaison, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health; January 25, Available from: http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/parry_romberg/parry_romberg.htm

- Sagild JC and Alving Hemiplegic migraine and progressive hemifacial atrophy; June 1985; 17(6): 620.

- Wolf SM and Verity Neurological complications of progressive facial hemiatrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974 Sep; 37(9): 997–1004.

- Asher SW and Berg Progressive hemifacial atrophy: Report of three cases, including one observed over 43 years, and computed tomography findings. Arch Neurol. 1982; 39: 44-46.

Faculty Reviewer: Griffin Jardine, MD

Copyright statement: Copyright 2017. Please see terms of use page for more information.

Band Keratopathy

Home / External Disease and Cornea / Clinical Approach to Depositions and Degenerations of the Conjunctiva, Cornea, and Sclera

Title: Band Keratopathy Case Report

Author: Martin de la Presa, BA

Photographer: unknown

Date: 8/18/2015

Keywords / Main Subjects: Band keratopathy; calcium hydroxyapatite deposition

Diagnosis / Differential Diagnosis: Interstitial keratitis; calcareous degeneration; calciphylaxis

Secondary CORE Category: Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis / Complications of Uveitis

Brief Description of Image: Band keratopathy is the pathological deposition of calcium within the superficial layers of the cornea, specifically Bowman’s layer. The condition ranges from asymptomatic to causing ocular irritation, foreign body sensation and decreased vision. Though it is often idiopathic there is a broad differential of local and systemic associated diseases. The local causes include chronic ocular irritation or inflammatory conditions such as chronic anterior uveitis (especially in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis), interstitial keratitis, superficial keratitis, phthisis bulbi, end-stage glaucoma and silicone oil left in the aphakic eye. Systemic diseases associations include those diseases that elevate serum calcium levels such as in hyperparathyroidism, sarcoidosis, multiple myeloma, hypophosphatemia, Paget disease and chronic renal failure.

On exam, there is a white band-like formation of calcium across the corneal surface with irregular boarders and a peripheral clearing of cornea between the calcium deposits and the limbus. The calcium deposition is typically found beneath the epithelial layer within Bowman’s layer but may extend into anterior stroma. In the absence of an explainable local etiology laboratory testing is recommended to assess serum calcium and phosphate levels and renal function. When symptomatic, the calcium deposits can be removed with superficial debridement and manual scraping of the corneal surface with or without the aid of a chelating agent such as ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). Recurrence is common unless the predisposing cause is identified and treated.

Faculty Approval: Griffin Jardine, MD

Identifier: Moran_CORE_23763

References:

Copyright statement: Copyright 2017. Please see terms of use page for more information.

Episcleritis Associated with Lyme Disease

Home / External Disease and Cornea / Diagnosis and Management of Immune-Related Disorders of the External Eye

Title: Episcleritis Associated with Lyme Disease, Case Report

Author: Eliza Barnwell, MSCR

Photographer: unknown

Date: 9/19/16

Secondary CORE Category: Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis / Noninfections (Autoimmune) Uveitis

Keywords / Main Subjects: Episcleritis; scleritis; conjunctival inflammation

Diagnosis: Episcleritis

Description of Image: This patient is a 24–year-old male with a one year history of Lyme disease who presented with 2 months of light sensitivity, redness and irritation in the right eye. Slit-lamp examination of the right eye revealed mild ptosis, 2+ sectoral injection of the conjunctiva in the superior and nasal regions with dilated episcleral vessels and 3 cells per high-powered-field in the anterior chamber. Examination of his left eye was normal. Topical application of 2.5% phenylephrine blanched the injected vessels. He was started on prednisolone drops 4 times a day and the episcleritis resolved shortly thereafter.

Episcleritis is typically an idiopathic, autoimmune condition causing dilation and inflammation of the superficial layers of the eye.1 Although usually idiopathic, episcleritis can also be associated with a variety of systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematous (SLE) and Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).3 Though uncommon, a number of studies have described episcleritis as an ocular manifestation of Lyme disease, both in late and early stages of the disease.4,5,6 In one case report, initiation of intravenous ceftriaxone therapy aggravated episcleral inflammation and caused an anterior chamber reaction in a patient with positive serum titers for Lyme.7

Scleritis is a deeper inflammation of the scleral vessels that typically does not blanch with application of topical phenylephrine. It is often associated with a systemic autoimmune disease in contrast to episcleritis. Scleritis tends to have dramatic focal tenderness and in its more severe form can lead to scleral thinning and perforation.

Treatment for scleritis commonly involves systemic anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive agents, while episcleritis often resolves on its own or can be treated with a short course of topical steroids versus oral NSAIDs.2

Format: image

Identifier: Moran_CORE_23749

References:

- Jabs DA, Mudun A, Dunn JP, Marsh MJ. “Episcleritis and scleritis: clinical features and treatment results.” American journal of ophthalmology. 2000;130(4):469-76.

- Kirkwood BJ, Kirkwood RA. “Episcleritis and scleritis.” Insight. 2010;35(4):5.

- Akpek EK, Uy HS, Christen W, Gurdal C, Foster CS. “Severity of episcleritis and systemic disease association.” Ophthalmology. 1999;106(4):729-31.

- Flach AJ, Lavoie PE. “Episcleritis, conjunctivitis, and keratitis as ocular manifestations of Lyme disease.” Ophthalmology. 1990;97(8):973-5.

- de la Maza MS, Molina N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Doctor PP, Tauber J, Foster CS. “Clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with scleritis and episcleritis.” Ophthalmology. 2012;119(1):43-50.

- Zaidman GW. “Episcleritis and symblepharon associated with Lyme keratitis. American journal of ophthalmology. 1990;109(4):487-8.

- Mikkilä HO, Seppälä IJ, Viljanen MK, Peltomaa MP, Karma A. “The expanding clinical spectrum of ocular lyme” Ophthalmology. 2000;107(3):581-7.

Faculty Approval By: Dr. Amy Lin, Dr. Severin Pouly and Dr. Griffin Jardine

Ocular Candidiasis

Home / Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis / Endophthalmitis

Loading...

Loading...

Title: Ocular Candidiasis

Authors: Christopher D. Conrady, MD, PhD, Rachel Jacoby, MD, Akbar Shakoor, MD, and Paul Bernstein MD, PhD

Date: 11/2016

Keywords/Main Subjects: candidiasis, endophthalmitis, fungal endophthalmitis

Diagnosis/Differential Diagnosis: Presumed Candida endophthalmitis

Brief Description of Case: In the following cases, we present a 13-year-old boy that was being treated for B cell ALL. He developed a fever of unknown origin and was subsequently found to have GI imaging findings consistent with systemic candida. Blood cultures remained negative. Due to concern for candida, ophthalmology was asked to evaluate the patient and he was subsequently found to have two chorioretinal lesions of the left eye. He was initially closely monitored on IV antifungal therapy but then required intraocular injections, and finally, a pars plana vitrectomy due to re-activation of the lesions. Unfortunately, no microbiology could help direct therapy in this case and the full case is seen in detail in the presentation.

Images:

Slides 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 14, and 17 are dilated fundus photographs. Slide 14 specifically shows the re-activation of the lesion once the patient was transitioned to oral antifungals as seen with the hazy borders and enlarged size compared to prior images.

Slide 21: Denotes a second case of presumed candida fungal endophthalmitis in a 10-year-old boy being treated for ALL. He has two notable peripheral lesions in the left eye. Due to their non-central nature, the spots were monitored closely and remained unchanged while on anti-fungal therapy. His other eye (not shown) had a foveal-involving lesion that required intravitreal antifungal therapy in addition to systemic antifungals.

Summary of Cases:

These two cases highlight the medical and surgical management of fungal endophthalmitis.

References for further reading:

- Brod RD, Flynn HW Jr., Clarkson JG, Pflugfelder SC, Culbertson WW, Miller D. Endogenous Candida endophthalmitis: management without intravenous amphotericin B. Ophthalmology 1990;97:666-72.

- Essman TF, Flynn HW Jr, Smiddy WE, Brod RD, Murray TG, Davis JL. Treatment outcomes in a 10-year study of endogenous fungal endophthalmitis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1997 Mar. 28(3):185-94.

- Hariprasad SM, Mieler WF, Holz ER, et al. Determination of vitreous, aqueous, and plasma concentration of orally administered voriconazole in humans. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:42-7.

- O’Day DM, Head WS, Robinson RD, Stern WH, Freeman JM. Intraocular penetration of systemically administered antifungal agents. Curr Eye Res 1985;4:131-4.

- Paulus YM, Cheng S, Karth PA, Leng T. PROSPECTIVE TRIAL OF ENDOGENOUS FUNGAL ENDOPHTHALMITIS AND CHORIORETINITIS RATES, CLINICAL COURSE, AND OUTCOMES IN PATIENTS WITH FUNGEMIA. Retina. 2015 Dec 11.

- Riddell et al., Treatment of Endogenous Fungal Endophthalmitis: Focus on New Antifungal Agents. Clinc Inf Dis.

- Schmid S, Martenet AC, Oelz O. Candida endophthalmitis: clinical presentation, treatment and outcome in 23 patients. Infection 1991;19:21-4.

- Sridhar J, Flynn HW Jr, Kuriyan AE, Miller D, Albini T. Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis: risk factors, clinical features, and treatment outcomes in mold and yeast infections. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013 Sep 20. 3 (1):60.

- Tod M, Lortholary O, Padoin, Chaine G. Intravitreous penetration of fluconazole during endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Infect 1997;3:379A.

- Walsh TJ, Foulds G, Pizzo PA. Pharmacokinetics and tissue penetration of fluconazole in rabbits. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1989;33:467-9.

Copyright statement: Christopher D. Conrady, ©2016. For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: URL to copyright information page on Moran CORE

Under Review

A Case Report of Hypertensive Retinopathy

Home / Retina and Vitreous / Other Retinal Vascular Diseases

Title: A Case Report of Hypertensive Retinopathy

Author: Tyler Scott Quist, BS

Photographer: James Gilman

Date: 08/2016

Keywords/Main Subjects: Hypertensive retinopathy, hypertensive emergency

Introduction:

Hypertensive retinopathy refers to the microvascular changes of the retina that occur in the setting of hypertension and is a common cause of ocular disease. Hypertensive emergency refers to a systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 180 and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 120 with evidence of end organ damage, such as retinopathy.

Case Report:

A 40-year-old male with a history of newly diagnosed systolic blood pressure over 200 presents with a three-week history of bilateral blurry vision and halos worse in the left eye. The patient reported new-onset migraines and denied any other ocular symptoms. On exam, his visual acuity was 20/25 and 20/150 in the right and left eye, respectively. Tonometry, pupils, visual fields, extraocular movements, and slit lamp exam were unremarkable. The fundus exam was remarkable for bilateral optic disc edema and hemorrhage, macular hemorrhages and exudates, and arteriolar narrowing as shown in Figure 1. The patient was sent to the emergency department, where magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a small stroke in the corpus collosum. The patient was treated for hypertensive emergency with antihypertensives and his vision slowly improved over the course of several months.

Figure 1: Hypertensive retinopathy in the right eye remarkable for bilateral optic disc edema and hemorrhage, macular exudates and hemorrhages, as well as arteriolar narrowing.

Discussion:

Hypertension results in retinal microvascular changes called hypertensive retinopathy, which may be categorized as mild, moderate, or severe. The mild form is characterized by retinal arteriolar narrowing, the moderate form is characterized by hemorrhages and exudates, and the severe form is characterized by optic disc edema1. Hypertensive retinopathy is more common with increased age and among black persons and has a prevalence rate from two to fifteen percent1. Patients with malignant hypertensive retinopathy may present with blurry vision, decreased visual acuity, eye pain, and headaches. The dilated fundoscopic exam and coexisting hypertension is paramount in establishing the correct diagnosis and classification of the disease. Previously published literature has shown that reducing systemic blood pressure below 140/90 mmHg improves hypertensive retinopathy2,3. However, it is uncertain whether antihypertensive agents with a direct effect on microvasculature have any benefit over other antihypertensive medications.

References:

- Wong TY, Mitchell P. Hypertensive retinopathy. N Engl J Med 2004;351:2310.

- Bock KD. Regression of retinal vascular changes by antihypertensive therapy. Hypertension 1984;6:III-158.

- Dahlof B, Stenkula S, Hansson L. Hypertensive retinal vascular changes: relationship to left ventricular hypertrophy and arteriolar changes before and after treatment. Blood Press 1992;1:35-44.

Faculty Approval By: Dr. Amy Lin

Footer: Copyright 2016, Tyler Scott Quist. For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: http://morancore.utah.edu/terms-of-use/

Identifier: Moran_CORE_21698

Disclosure (Financial or other): No authors have any financial or proprietary interest in any material or methods mentioned.

UNDER REVIEW

Opthalmoplegic Migraine / Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy

Home / Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus / Special Forms of Strabismus

Title: Opthalmoplegic Migraine / Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic neuropathy

Date: 09/2015

Keywords: Opthalmoplegic Migraine, Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic neuropathy

Images:

Case Report:

Chief Complaint: Lid drooping and drifting eye

History of Present Illness: 3 year 3month old girl with past medical history of oculomotor nerve palsy (episode 2 years prior, resolved) presents with recurrent symptoms of oculomotor palsy. Four days prior, she experienced a GI illness with vomiting and decreased energy. Her parents deny fever, upper respiratory infection, cough, eye pain, rash or HA. The GI illness resolved two days later and around the same time her right upper eyelid began to droop. Over the next two days the drooping progressed and the patient developed deviated eye and asymmetric pupils. Her previous episode of oculomotor nerve palsy developed much like the present one. The parents report a sub-acute onset over a few days that progressed from ptosis, to anisocoria and strabismus. The episode resolved without treatment over about one week. An MRI was performed at an outside hospital and the read was as follows: “Enhancement of the right third cranial nerve which is most prominent immediately adjacent to the origin of the nerve at the brain stem. The enhancement extends anteriorly along the nerve to the cavernous sinus.” Her clinical presentation and imaging were felt to be consistent with inflammatory neuritis, most likely post viral.

Past Medical History: Otherwise non-contributory

Past Surgical History: None

Medications: None

Allergies: No known drug allergies

Immunizations: Up to date

Development: Age appropriate

Family History: No family history of eye disease, migraine, MS, neurologic disease, childhood cancers. Maternal cousins with celiac disease and DM1

Social History: Lives with parents; 2 cats and a dog. Attends daycare

Review of Symptoms: All negative except as above

Ocular Physical Exam:

- General: Alert and oriented, NAD

- isual Acuity: Fix and Follow OU

- Pupils

- OD: 5mm > 4mm

- OS: 4mm > 2mm

- EOM

- Primary gaze: right eye deviated inferiorly and temporally

- OD:

- -3 adduction

- -2 elevation

- -1 depression

- -0 abduction

- OS:

- Full EOM

- Penlight

- Orbits: No deformities, ecchymosis or edema

- Lids/Lashes: Right ptosis, MRD1 0.5mm, normal eyelid position OS

- Conjunctiva/Sclera: white and quiet OU

- Cornea: clear OU

- Anterior Chamber: formed without hyphema or hypopyon OU

- Iris: flat and round OU

- Lens: WNL OU

- Dilated Fundus exam:

- Optic Nerve: sharp margins, no disc edema

- Macula: Healthy OU

- Vessels: Normal caliber OU

- Periphery: WNL OU

Vital signs and labs:

- T: 36.8

- HR: 104

- RR: 24

- BP: 112/60

- Sat: 99% RA

- CRP, BMP CBC: within normal limits

Imaging:

Image 1: Axial MRI T1 with contrast showing enhancement of the right 3rd nerve in the cisternal segment.

Image 2: Coronal MRI T1 with contrast showing enhancement and thickening of the cisternal portion of the right oculomotor nerve.

Differential:

- Post-Viral Neuritis

- Ophthalmoplegic migraine/Recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy

- Aneurysm

- Schwannoma

- Tolosa-Hunt

- ADEM

- Miller-Fisher Syndrome

- TB, Lyme, Sarcoid, Lymphoma

Case Discussion:

Based on clinical presentation, the list of differential diagnoses for our patient’s third nerve palsy would be quite extensive. ADEM and Miller-Fischer syndrome can present as third nerve palsies but they would also tend to be accompanied by other neurologic deficits such as ataxia or areflexia. When the recurrent and resolving history is taken into account aneurysm, schwannoma, TB, Lyme, sarcoid, and lymphoma become less likely as these would tend to be slowly progressive and unlikely to resolve without treatment. Imaging confirms the absence of schwannoma and also rules out Tolosa-hunt which would show inflammation in the cavernous sinus and meningeal enhancement. Aneurysm, Tolosa-Hunt, and Miller-Fisher syndrome would also be quite rare in this age group.

With all of these factors taken together the most likely diagnosis is either post-viral neuritis or Ophthalmoplegic migraine/Recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy (OM/RPON). It is possible that these two conditions are related.

Epidemiology

OM/RPON is a rare condition with a prevalence of 0.7 per million6; it usually begins in childhood.2,3 A systematic review authored by Gelfand found a median age of onset at 8 years old (interquartile range 3, 16). They also found that approximately 2/3 of patients affected by OM/RPON were female. 4

Signs and Symptoms

OM/RPON typically presents as a headache followed ophthalmoplegia. If headache is present, it is typically unilateral and ipsilateral to the affected eye. The headache may or may not have migrainous features; accompanied by photophobia, phonophobia, or nausea/vomiting. The ophthalmoplegia can occur immediately or up to 14 days after the headache. One or multiple nerves may be affected. The frequency of nerves affected in Gelfand’s paper was CNIII 83%, CNVI 20%, and CNIV 2%. If multiple nerves were affected, CNIII was always included.4 When CNIII is affected it may be a partial or complete palsy. Both ptosis and mydriasis are common, especially among children.

Diagnostic Criteria:

According to the International Classification of Headache Disorder 3-beta1:

A. At least Two attacks fulfilling criterion B.

B. Unilateral headache accompanied by ipsilateral paresis of one, two or all three ocular motor nerves.

C. Orbital, parasellar, or posterior fossa lesion has been excluded by appropriate investigation.

D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 dx

As stated above, before the diagnosis of OM/RPON is made it is very important to rule out other possible etiologies such as aneurysm, schwannoma, granulomatous disease, and inflammatory neuropathy.2

Pathophysiology:

The pathophysiology of OM/RPON is a topic of ongoing debate. The diagnostic criteria in ICHD have been updated over the years to mirror the trends in the etiologic discussion by classifying it first as a migraine, then as a neuralgia, and most recently as a neuropathy.5 In fact, with the newest release of ICHD-3beta, the International Headache Society recommended the term ‘ophthalmoplegic migraine’ be abandoned.1 The driving force for this progression has been the need to explain the reversible contrast enhancement at the root entry zone of the affected cranial nerve.

Some who support the viewpoint of a neuropathy will point to the possibility of a benign neurotropic viral infection and highlight the similarities of the imaging in OM/RPON to those found in Bell’s Palsy.2 Others advocate for an immune-mediated neuropathy similar to chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).5 In both of these explanations, the headache of OM/RPON is a result of inflammation of the nerve. The inflammation causes vasoconstriction of the nearby vasculature subsequently triggering the headache. However, these hypotheses are not without their weaknesses, CSF analysis and viral studies typically return unremarkable in OM/RPON.

Even with the current trend towards viewing OM/RPON as a neuropathy, there are still some who continue to advocate for a migrainous etiology. A paper published in 2014 proposed that a migraine induced vasospasm of the arteries supplying CNIII, IV, or VI could lead to ischemia of the nerves causing reversible breakdown of the nerve-blood barrier allowing for contrast extravasation and subsequent nerve enhancement on MRI.3 The authors make a great case, yet still leave questions unanswered. If migraine is the causal process then why does treatment with acute and prophylactic migraine medication offer little to no benefit or protection to patients?

In summary, there is still much work to be done towards reaching an understanding of how and why OM/RPON occurs. It is valuable to consider that OM/RPON may in fact have a multifactorial etiology resulting from processes and predispositions related to both neuropathy and migraine.

Treatment: With such ambiguity clouding the pathophysiology of OM/RPON it follows that there is also uncertainty regarding effective treatment for the condition. Migraine medications both acute and prophylactic have been tried with unconvincing efficacy while the results of steroids have been positive yet mixed. Gelfand found steroids to be beneficial in 54% of cases reviewed. Yet the effects were either unclear, not beneficial or even harmful in 35%, 8%, and 4% respectively.4

Prognosis: Prognosis in OM/RPON is generally excellent and most patients can experience a full recovery in days to weeks. However small minority of patients may be left with

persistent neurological deficits, especially those who suffer from repeated attacks.2,3,4,5

References

1. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version).

2. Alexander, et. Al. Ophthalmoplegic Migraine: Reversible Enhancement and Thickening of the Cisternal Segment of the Oculomotor Nerve on Contrast-Enhanced MR Images. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 19:1887–1891, November 1998

3. Ambrosetto, et. Al. Ophthalmoplegic migraine: From questions to answers. Cephalalgia 2014, Vol. 34(11) 914–919

4. Gelfand, et. Al. Ophthalmoplegic ‘‘Migraine’’ or Recurrent Ophthalmoplegic Cranial Neuropathy: New Cases and a Systematic Review.

Identifier: Moran_CORE_21686

Financial Disclosure: None

Vitreitis Secondary to CNS Lymphoma

Home / Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis / Masquerade Syndromes /

Title: Vitreitis Secondary to CNS Lymphoma

Authors: Michael Simmons, BS

Photographer: Melissa Chandler

Date: 07/27/2016

On presentation, the patient had disc edema and a small optic nerve hemorrhage at 2 o’clock.

Fluorescein angiography demonstrated leakage from the optic nerve. Vitreitis was also noted.

Keywords / Main Subjects: CNS lymphoma; Disc edema; vitreitis

Diagnosis: Central nervous system extranodal natural killer cell/t-cell lymphoma (ENKTL) with optic nerve involvement and left vitreitis

Brief Description of Image: Extranodal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma (ENKTL) is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma [1]. It makes up approximately 1% of all lymphomas in the US, but may occur more frequently in Hispanics and Native Americans[2]. It has a close association with Epstein-Barr virus infection and typically manifests in the nasal cavity [3]. ENKTL is an aggressive disease with a poor prognosis [4]. There is a tendency to metastasize to the central nervous system [2]. Although rare, ocular involvement has been noted[5][6]. Ocular symptoms are nonspecific, and include such entities as eyelid edema and ptosis, blurred vision, optic nerve swelling, and steroid refractory anterior uveitis and vitreitis [2,5,7].

The patient is a 38-year-old man with a 26-year history of extranodal natural killer cell/T-cell lymphoma with multiple recurrences including central nervous system recurrences despite allogeneic bone marrow transplant. He presented for evaluation of six weeks of floaters and a new blind spot in his left eye. On exam, he was found to have diminished visual acuity with a 0.6 log left afferent pupillary defect, but color vision testing with Ishihara plates and a flicker fusion test were normal. He was found to have an intraocular pressure in his left eye. On slit lamp exam, there were 2+ cells in the left anterior chamber and 3+ vitreous cells with a pre-papillary and pre-macular vitreous infiltrate. There was also grade II disc edema. Fluorescein angiography showed no evidence of retinitis, but there was bilateral disc leakage, more prominent on the left than the right.

Flow cytometry performed on the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid revealed 20% abnormal natural killer cells lacking CD16 with prominent expression of CD57. Labs investigating alternate etiologies, including tuberculosis, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, bartonellosis, Lyme disease and sarcoidosis were negative. Previous therapies included chemotherapy, radiation therapy, infusions of EBV-specific T-cells, and allogeneic bone marrow transplant. With his current relapse, the patient received palliative external radiation therapy of the head and intrathecal cytarabine. The team also renewed discussions regarding hospice and end-of-life care.

References:

- Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17: 3835–3849.

- Cimino L, Chan C-C, Shen D, Masini L, Ilariucci F, Masetti M, et al. Ocular involvement in nasal natural killer T-cell lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2009;29: 275–279.

- Li S, Feng X, Li T, Zhang S, Zuo Z, Lin P, et al. Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type: a report of 73 cases at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37: 14–23.

- Hatta C, Ogasawara H, Okita J, Kubota A, Ishida M. Non-Hodgkin’s malignant lymphoma of the sinonasal tract—treatment outcome for 53 patients according to REAL classification. Auris Nasus Larynx. Elsevier; 2001; Available: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0385814600000948

- Abe RY, Pinto RDP, Bonfitto JFL, Lira RPC, Arieta CEL. Ocular masquerade syndrome associated with extranodal nasal natural killer/T-cell lymphoma: case report. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2012;75: 430–432.

- Maruyama K, Kunikata H, Sugita S, Mochizuki M, Ichinohasama R, Nakazawa T. First case of primary intraocular natural killer t-cell lymphoma. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15: 169.

- Yoo JH, Kim SY, Jung KB, Lee JJ, Lee SJ. Intraocular involvement of a nasal natural killer T-cell lymphoma: a case report. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2012;26: 54–57.

Disclosure (Financial or other): None

Identifier: Moran_CORE_21679

UNDER REVIEW