Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) Disease Case Report

Home / Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis / Noninfections (Autoimmune) Uveitis

Title: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) Disease Case Report

Author: Taylor Johnson, MSIV, University of Utah Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine

Date: 8/10/2024

Keywords/Main Subjects: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease, uveitis

Diagnosis: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) Disease

Images:

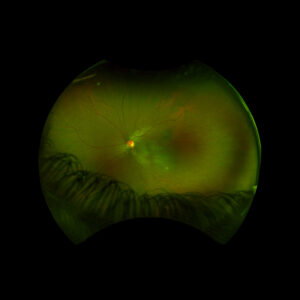

Figure 1: Wide field fundus photo of the left eye showing subretinal fluid and a hypo-pigmented choroidal elevation centrally and inferotemporally. Note an unrelated choroidal nevus along the superotemporal arcade.

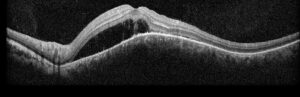

Figure 2: Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the left eye with subretinal fluid and choroidal elevation.

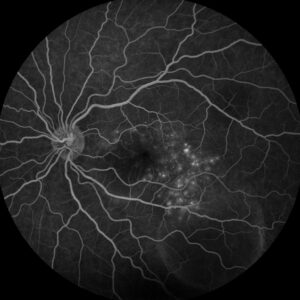

Figure 3: Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the left eye at 07:20 demonstrating hyperfluorescent punctate spots overlying the inferotemperal lesion.

Description of Case:

An 18 year old female of Mexican descent presented after waking up with a headache in the frontal region and behind the left eye. Subsequently, she noted an enlarging dark spot in her left eye’s vision. She denied any previous ocular history. Medical history was notable for class IV obesity and asthma.

Right eye exam was unremarkable. Left eye exam was notable for rare pigmented vitreous cell, subretinal fluid, as well as a hypo-pigmented choroidal elevation centrally and inferotemporally, confirmed on optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Fig 1 &2). Fluorescein angiography (FA) demonstrated late hyperfluorescent punctate spots overlying the inferotemperal lesion (Fig 3). B scan confirmed choroidal thickening without a discrete mass.

Early Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada was suspected, with the differential also including non-pigmented choroidal tumor infectious etiology. Labs to rule out infectious etiology were negative. Treatment was initiated with a prednisone taper, and the patient’s visual acuity, subretinal fluid, and choroidal elevation were greatly improved the following week, supporting the diagnosis. The patient went on to develop recurrences in subsequent years, requiring further prednisone tapers and the addition of immunomodulatory therapy (methotrexate).

Overview:

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VHK) disease is characterized by bilateral granulomatous panuveitis and systemic manifestations related to T-cell mediated autoimmune attacks of melanocytes in the eyes, ears, meninges, skin, and hair.1 It is most commonly seen in darkly pigmented populations (especially individuals of Asian, Hispanic, and Middle Eastern descent), in women, and in younger adults.2,3 In the United States, it is a rare cause of uveitis, making up only 3-4% of referrals to tertiary care centers.4 Clinically, VKH disease presents in four different phases: prodromal, acute uveitic, convalescent, and chronic recurrent.

The prodromal phase includes mostly extraocular manifestations, such as headache, flu-like symptoms, meningismus, tinnitus, and hearing loss.5

Days to weeks later, features of acute uveitis manifest suddenly and bilaterally, beginning with the posterior segment and potentially spreading to the vitreous and anterior segment if untreated.1 Posterior pole signs include areas of subretinal fluid and choroidal thickening, leading to breakdown of the retinal pigment epithelium and the disease’s characteristic serous retinal detachments.1

In the convalescent stage, inflammation subsides, leaving behind a depigmented fundus often described as a “sunset glow.”3

Some patients develop chronic recurrences of granulomatous anterior uveitis that are resistant to steroids and can involve a myriad of complications, including cataract, subretinal fibrosis, chorioretinal atrophy, choroidal neovascular membrane, and glaucoma.6

Systemic manifestations:

Besides the ophthalmic symptoms and complications, patients with VKH disease can often develop systemic findings related to autoimmune targeting of melanocyte antigens. Signs and symptoms include depigmentation of the eyebrows, eyelashes, and scalp, alopecia, poliosis, CSF pleocytosis, headache, and hearing manifestations such as sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, dysacusis, and a sensation of fullness in the ear.1,7

Workup and Diagnosis:

The diagnosis of VKH is based on clinical findings as above in combination with the absence of penetrating trauma or surgery to the eye or a more likely diagnosis based on clinical and laboratory findings, with ancillary investigations commonly including fluorescein angiography (FA), indocyanine green angiography (ICGA), optical coherence tomography (OCT), ultrasonography, electroretinography (ERG), and cerebrospinal fluid analysis.3

Treatment:

Early treatment with high-dose systemic corticosteroids is crucial to manage the acute stage of VKH, with slow tapering to prevent recurrence.5 More recent data has shown better outcomes with the addition of local steroid injections and/or implants to treat refractory ocular symptoms, and immunomodulatory therapy (IMT) to treat systemic manifestations while sparing patients from complications of systemic steroids in the long-term.1,7

Prognosis:

The visual prognosis of VKH depends heavily on the stage in which it presents. Early treatment in the acute stage is associated with a good visual prognosis and even cure, while chronic recurrent disease is often refractory to treatment and prone to complications such as choroidal neovascular membrane, glaucoma, cataract, and chorioretinal atrophy.6

Summary of the Case:

Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VHK) disease is a form of granulomatous panuveitis that targets melanocytes. In the acute stage, posterior uveitis with subretinal fluid and choroidal thickening predominates along with hearing, neurologic, and integumentary changes. The chronic stage is characterized by anterior uveitic recurrences and ocular complications. Early control with high-dose steroids and possibly IMT is critical for an optimal prognosis.

References:

- O’Keefe GAD, Rao NA. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2017;62(1):1-25. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.05.002

- Read RW, Holland GN, Rao NA, et al. Revised Diagnostic Criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease: Report of an International Committee on Nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131(5).

- Tayal A, Daigavane S, Gupta N. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease: A Narrative Review. Cureus. Published online April 23, 2024. doi:10.7759/cureus.58867

- Ohno S, Char DH, Kimura SJ, Richard O’Connor G. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83(5):735-740. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(77)90142-8

- Lodhi S, Reddy L, Perum V. Clinical spectrum and management options in Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;Volume 11:1399-1406. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S134977

- Urzua CA, Herbort C, Valenzuela RA, et al. Initial-onset acute and chronic recurrent stages are two distinctive courses of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2020;10(1):23. doi:10.1186/s12348-020-00214-2

- Stern EM, Nataneli N. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Accessed August 6, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574571/

Faculty Approval by: Akbar Shakoor, MD

Copyright statement: Copyright Taylor Johnson, ©2024. For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: http://morancore.utah.edu/terms-of-use/