A Man with Bilateral Vision Loss

Title: A Man with Bilateral Vision Loss

Authors: Samuel W. Wilkinson1, MD, Ashley Polski , MD, Roger P. Harrie1, MD

Date: 6/18/24

Keywords/Main Subjects: Meningioma, disc edema, proptosis

Diagnosis: Atypical meningioma

Description of Case:

A 72-year-old male presented to the university ophthalmology triage clinic with a 3-week history of severe visual loss in his right eye and a recent mild dimming of vision in his left eye. During a prior workup with a retinal specialist, he was reportedly found to have right optic disc edema in the setting of normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP). The retinologist suspected non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION) in the right eye and told the patient there was no treatment. His past medical history included essential hypertension, cataract surgery, and rheumatoid arthritis treated with daily 400 mg of hydroxychloroquine for 13 years. Examination of his right eye found visual acuity of count fingers at 1 meter with a 3+ afferent pupil defect and moderate optic disc edema. Vision in the left eye was 20/50 with a normal appearing optic disc. Intraocular pressures were 15 mmHg in both eyes. He was a moderate myope and had 2 mm proptosis of his right eye with a mild abduction deficit. A 24-2 Humphrey visual field test showed black-out on the right and moderate generalized depression on the left.

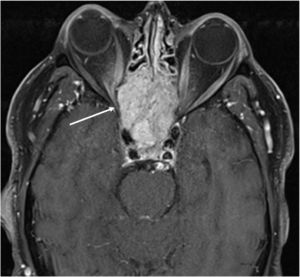

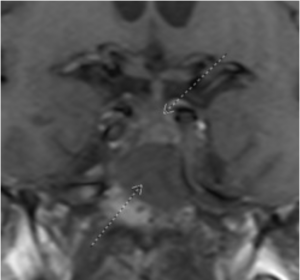

The patient was referred to the emergency department for a brain and orbital MRI scan, which showed a 5.2 x 3.4 x 4.5 cm mass centered in the sella, most compatible with an invasive pituitary macroadenoma (Figures 1 and 2). The mass invaded the skull base and extended into the right more than the left optic canals and into the right posterior extracortical space at the orbital apex. It also displaced the right more than the left optic nerve cisternal and canalicular segments. There were no findings of cavernous sinus invasion. The patient underwent a combined neurosurgery and otolaryngology procedure with debulking of the tumor. The pathology report was consistent with a grade II atypical meningothelial meningioma.

Discussion:

Meningiomas are the most common primary central nervous system tumor which comprise over 50% of benign tumors in the brain and spinal cord. The average age at diagnosis is 66 years old and they occur in women about twice as often as men. They tend to be more malignant when they occur in men and even more so in children.1 They arise from meningeal arachnoid cells and up to 2% of autopsies find meningiomas that were unknown to the patient during life because they were asymptomatic. They are categorized histologically into WHO grades I, II, and III based on increasing malignancy.2 The ten year survival rates are 84% for grade I, 53% for grade II, and 0% for grade III. The patient described in this report had a Grade II atypical meningioma with a 5 year recurrence rate of 50 to 55%. Treatment includes observation for asymptomatic tumors, surgical resection, and radiation.3

Patients such as the one in our case with optic disc edema and bilateral vision loss must be evaluated for orbital and intracranial etiologies, particularly when proptosis is present. The initial impression of NAION in the patient’s right eye was inconsistent with subsequent decreased vision in the left eye with a normal appearance of the optic disc. Second eye involvement in NAION occurs in 15 to 17% of patients over five years, but the exam would usually demonstrate sectoral disc edema and altitudinal visual field loss.4 In some cases, sequential vision loss occurs from an intracranial mass causing optic atrophy in the ipsilateral eye and papilledema in the contralateral eye—a condition known as Foster-Kennedy syndrome.5 The patient in this report did not technically fit the criteria for Foster-Kennedy syndrome with papilledema in only one eye and a normal appearing optic disc in the other, but he could have potentially manifested this finding if surgical intervention had not occurred.

A temporal artery biopsy to evaluate for giant cell arteritis (GCA) should be considered in elderly patients with visual loss in one eye and impending loss in the opposite eye, particularly if there are signs of vascular compromise to the optic disc and/or retina or other manifestations of systemic inflammation.6 Extraocular motility deficits can also, in rare cases, occur in the setting of GCA.7 Our patient had normal inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP) and denied symptoms such as tenderness in the temples and jaw claudication. Additionally, the finding of proptosis would be atypical for GCA and points more towards a mass with orbital involvement.

In patients with proptosis or extraocular motility abnormalities for whom an intracranial/orbital mass has been ruled out, a thyroid antibody panel would be a reasonable next step in the work-up. Patients with thyroid eye disease can, in rare cases, experience vision loss and optic disc edema due to optic nerve compression. More common clinical findings of thyroid eye disease include eyelid retraction, extraocular motility restriction, and conjunctival injection.8 A macular OCT to analyze the ellipsoid zone is also a reasonable consideration given his 13 year history of hydroxychloroquine use that could cause a maculopathy.9 A macular OCT is also helpful in ruling out other retinal pathology such as age-related macular degeneration which is a leading cause of vision loss in older adults.10 However, our patient did not have any findings of retinal pathology on dilated fundus exam.

Patient Outcome:

He had his pituitary mass resected, which found a WHO grade 2 atypical meningioma. During a follow up visit in neuro-ophthalmology clinic two months after resection of his tumor, his best-corrected vision improved from count fingers at 1 meter to 5/200 in his right eye and from 20/50 to 20/20 in his left eye. His right optic nerve was pale without edema and his left optic nerve was normal. Goldmann visual field testing found a central island of vision with marked peripheral constriction on the right and a small arcuate defect on the left.

Images or video:

Figure 1: Coronal T1 view of a skull-based mass (inferior arrow) lying inferior to the optic chiasm (superior arrow)

Summary of the Case: A 72-year-old man referred with the diagnosis of NAION presented with severe visual loss in his right eye and recent mild dimming of vision in his left eye. Visual acuity OD was count fingers with moderate optic disc edema. Vision in the left eye was 20/50 with a normal optic disc. He had a 2 mm proptosis of his right eye with a mild abduction deficit. An MRI scan showed a large mass centered in the sella that compressed the right optic nerve. Pathology from surgical debulking of the tumor found a grade II atypical meningothelial meningioma.

References:

- Elefante A, Russo C, di Stasi M, Vola E, Ugga L, Tortora F, et al. Neuroimaging in meningiomas: old tips and new tricks. Mini-invasive Surg(2021) 5:7. doi: 10.20517/2574-1225.2020.102

- Buerki RA, Horbinski CM, Kruser T, Horowitz PM, James CD, Lukas RV. An overview of meningiomas. Future Oncol(2018) 14:2161–77. doi: 10.2217/fon-2018-0006

- Ogasawara C, Philbrick BD, Adamson DC. Meningioma: A Review of Epidemiology, Pathology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Future Directions. Biomedicines2021, 9(3), 319; https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines9030319

- Newman NJ, Scherer R, Langenberg P, et al. The fellow eye in NAION: report from the ischemic optic neuropathy decompression trial follow-up study. Am J Ophthalmol. Sep 2002;134(3):317-28. doi:10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01639-2

- Sanders MD. The Foster Kennedy sign. Proc R Soc Med. Jun 1972;65(6):520-1.

- Vodopivec I, Rizzo JF. Ophthalmic manifestations of giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). Feb 01 2018;57(suppl_2):ii63-ii72. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kex428

- Ross AG, Jivraj I, Rodriguez G, et al. Retrospective, Multicenter Comparison of the Clinical Presentation of Patients Presenting With Diplopia From Giant Cell Arteritis vs Other Causes. J Neuroophthalmol. Mar 2019;39(1):8-13. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000656

- Weiler DL. Thyroid eye disease: a review. Clin Exp Optom. Jan 2017;100(1):20-25. doi:10.1111/cxo.12472

- Yusuf IH, Sharma S, Luqmani R, Downes SM. Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Eye (Lond). 2017;31(6):828-845. doi:10.1038/eye.2016.298

- Guymer RH, Campbell TG. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. Apr 29 2023 401(10386):1459-1472. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02609-5

Faculty Approval by: Roger Harrie, MD

Copyright statement: Sam Wilkinson, Ashley Polski, Roger P. Harrie ©2024. For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: http://morancore.utah.edu/terms-of-use/