Anisocoria

Home / Basic Ophthalmology Review / Pupillary Exam

Title: Anisocoria

Author: Kaitlin Smith, 4th Year Medical Student, University of Missouri School of Medicine

INTRODUCTION

Anisocoria is defined as unequal pupil sizes—occasionally first noticed by a clinician but more commonly detected by the patient and brought to the clinician’s attention. The difference in size between two pupils should not typically be greater than 0.4 mm, therefore most any change that the patient or clinician notices would be abnormal—whether due to a benign or malignant etiology. Some of the associated causes of anisocoria have life-threatening implications. Thus, we hope to layout a framework and approach to assist in the triage and management of these patients.

HISTORY

Pertinent questions should include:

- Timing of Onset: Ask the patient for photos that precede the suspected date of onset as anisocoria can be noticed suddenly but may truly be longstanding or even congenital.

- History of trauma: Inquire about trauma specifically to the eye, head or neck.

- Social history: Determine if the patient has factors that would predispose them to lung pathology such as smoking.

- Medical history: Ask about strokes, sexually transmitted diseases (Syphilis), glaucoma or rheumatologic conditions.

- Current medications: Inquire specifically about medications with autonomic effects (e.g. scopolamine patch).

EXAMINATION

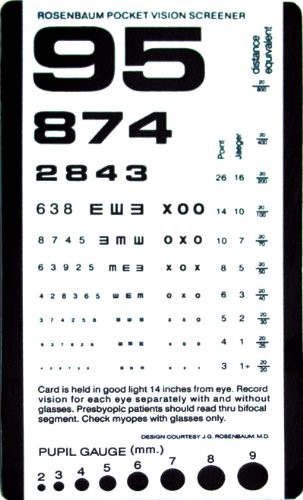

The pupils should be examined for shape, position, symmetry, reactivity, and size. Size is most easily determined with the help of a measurement tool that includes millimeter increments, included in many near acuity cards (Figure 1). Size of the pupil should be recorded in both light and dark conditions with the patient focusing on a target in the distance to avoid pupillary constriction associated with viewing targets at near (accommodation and the near triad). The pupillary response should also be observed at near to determine if the patient has a light-near dissociation. A halogen light is typically used to determine both direct response (the constriction of the pupil the light is being shone into) and consensual response (the constriction of the contralateral pupil when light is shone into the ipsilateral eye). The healthy pupil constricts to 2-4 mm in size when exposed to light and will dilate up to 4-8 mm in the dark.

Figure 1: Rosenbaum Pocket Vision Screener with a Pupil Gauge on the bottom for measuring pupil sizes.

The key to the pupillary exam in anisocoria is identifying whether the anisocoria is greater in light or dark conditions—this clues you in to which part of the autonomic system is affected. The sympathetic system dilates the pupil while the parasympathetic system constricts the pupil. Image 1 demonstrates one example of how to test and evaluate anisocoria.

Image 1: Example of a right sided parasympathetic defect. RLF = Room Light Far (focused on a distant target in light conditions). D15 = Dim lighting for 15 seconds. The anisocoria is greater in light suggesting impaired constriction of the right eye, or a parasympathetic defect.

EMERGENT DIAGNOSES

Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma

A fixed mid-dilated pupil associated with significant eye pain and redness suggests acute angle closure glaucoma. Checking the intraocular pressure (IOP) via a portable handheld pressure reading device, such as a Tono-pen®, would rule this in or out.

Sudden Onset 3rd Nerve Palsy

Anisocoria greater in light suggests an abnormally large pupil with impaired constriction or disrupted parasympathetic innervation. The parasympathetic fibers innervating the pupil travel with the 3rd cranial nerve, or oculomotor nerve. A sudden-onset dilated pupil associated with a droopy eyelid (ptosis) and abnormal eye position (strabismus – typically down and out) is highly suggestive of an acute 3rd cranial nerve (oculomotor) palsy. This could be caused by a potentially life-threatening posterior communicating artery aneurysm or impending uncal herniation. This presentation warrants immediately sending the patient to the emergency room for neuro-imaging and evaluation.

Sudden Onset Horner’s Syndrome

A Horner’s syndrome is characterized by anisocoria greater in dark, meaning an abnormally small pupil with impaired dilation or disrupted sympathetic innervation. It is often, though not always, part of a triad of signs, the other two being an ipsilateral droopy eyelid (ptosis), and lack of sweating (anhidrosis). The diagnostic challenge of a Horner’s Syndrome is that the lesion can be located anywhere along the sympathetic pathway. The most urgent and life-threatening etiology is a carotid artery dissection, but other serious causes may include a malignant lung tumor or spinal cord injury. Patients with an acute-onset Horner’s Syndrome need urgent imaging of the head, neck and upper lung that would include a study capable of detecting a carotid artery dissection, such as an MRA or CTA. Timely identification and treatment of a carotid artery dissection—including anticoagulation—can prevent a potential embolic stroke.

Physiologic Anisocoria

Over 20% of cases of anisocoria are the same in light and dark conditions and are benign, thus deemed, “physiologic anisocoria.” This condition typically presents with intermittent pupillary differences of less than 1 mm that are unchanged from light to dark and may be sporadic. It is thought to be caused by unequal inhibition of the parasympathetic pathway.

Conclusion

Anisocoria is an important exam finding that can be detected by an astute clinician who performs a careful and methodical pupillary exam. It is crucial for providers to be aware of the diagnostic steps to narrow a differential for anisocoria, as it can be a harbinger of treatable but life-threatening conditions. Below are two tables that include a broader differential for anisocoria.

Table 1: Anisocoria caused by parasympathetic defects

| Condition | Pathology | Triage |

| Adie’s tonic pupil | Idiopathic decrease in parasympathetic stimulation | Usually benign. Routine follow up in clinic with an ophthalmologist. |

| Trauma | Injury to the dilating muscles of the iris | If there is concern for head trauma, ruptured globe, hyphema or orbital fracture; consider obtaining CT and consulting ophthalmology. |

| Oculomotor nerve palsy | The parasympathetic fibers run on the outer portion of the nerve and thus are the first to be damaged in any compressive injury to the nerve. | CT and MRI should be obtained to rule out posterior communicating artery aneurysm, uncal herniation or an intracranial tumor. Urgent consultation and referral to neurology is typically warranted. |

| Pharmacologic Dilation | Agents such as scopolamine patches, inhaled ipratropium, nasal vasoconstrictors, and Jimson weed inhibit parasympathetics or activate sympathetics. | Non-urgent. Can typically be managed without referral. Determined by thorough history. Stop offending agent if causing light sensitivity and non-essential medication. |

Table 2: Anisocoria caused by sympathetic defects

| Condition | Pathology | Triage |

| Horner’s syndrome | Lesion along the sympathetic pathway from hypothalamus to lung to carotids. Common signs: constricted pupil & slight eyelid droop unilaterally. Less common signs: Lack of sweating and erythema unilaterally. | Urgent to determine location of the lesion with imaging along the sympathetic pathway or referral to an ophthalmologist as the cause can be life threatening. |

| Argyll-Robertson pupil | Bilateral pupils that constrict when viewing an object at near, but not with light stimulus typically due to tertiary syphilis | Obtain testing for syphilis (FTA-ABS). Would likely warrant admission for IV antibiotics to treat neurosyphilis. |

| Iritis | Inflammation in the eye can lead to adhesions from the pupil to the lens, causing impaired dilation. | Warrants urgent follow up in clinic with an ophthalmologist unless there are signs of acute angle closure glaucoma. |

| Pharmacologic Constriction | Agents such as pilocarpine, prostaglandins, opioids, clonidine, and organophosphate insecticides inhibit sympathetics or activate parasympathetics. | Non-urgent. Can typically be managed without referral. Determined by thorough history. Stop offending agent if bothersome to patient. |

RESOURCES

- Demyelinating Optic Neuritis – EyeWiki. http://eyewiki.aao.org/Anisocoria. Published February 13, 2016. Accessed July 16, 2018.

- Gross JR, Mcclelland CM, Lee MS. An approach to anisocoria. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2016;27(6):486-492. doi:10.1097/icu.0000000000000316.

- Ronquillo N. Anisocoria. Moran Eye Center Resident Lectures. June 2018.

- DonRaphael W. Pupils – Approach and Cases. Moran Eye Center Resident Lectures 2017. June 2018.

- Foroozan R, Vaphiades M. The pupil. In: Kline’s Neuroophthalmology Review Manual . 8th ed. NJ: SLACK Incoporated; 2018:129-142.

Identifier: Moran_CORE_25489