Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma

Home / Basic Ophthalmology Review / Anterior Chamber

Title: Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma

Author (s): Troy Teeples, 4th year medical student, University of Utah School of Medicine; Griffin Jardine, MD

Image Designer: Troy Teeples, MSIV University of Utah School of Medicine

Date: 8/7/2018

Keywords/Main Subjects: Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma, painful eye, red eye, pupillary block, halos

Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma

What is it?

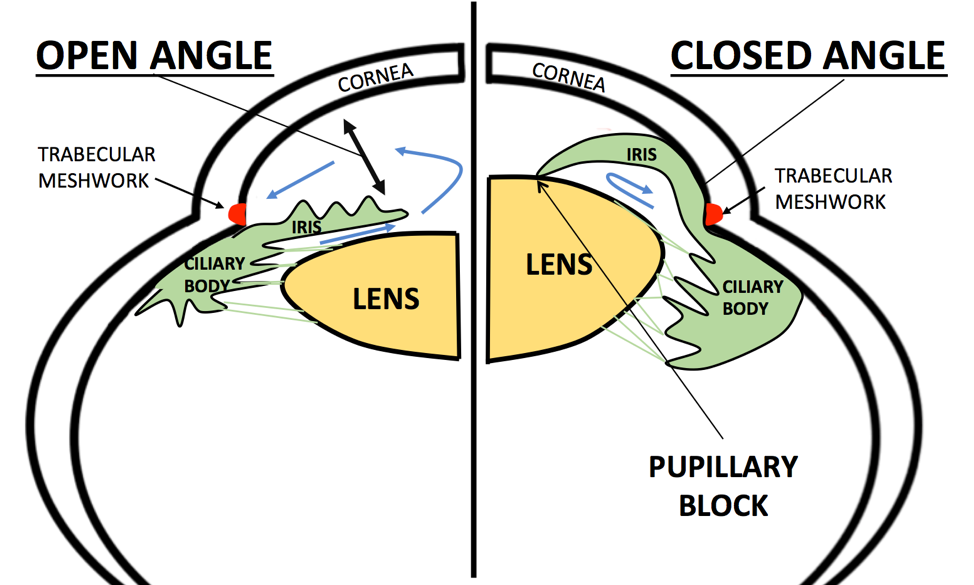

Angle-closure glaucoma is a group of diseases in which the angle of the anterior-chamber (the fluid-filled space between the iris and the cornea) closes, which can occur both acutely and chronically. Acute angle-closure glaucoma (AACG) is an ophthalmologic emergency where the intraocular pressure (IOP) rises rapidly due to a sudden blockage of the trabecular meshwork, which normally functions to drain the aqueous humor of the eye. AACG can subsequently be divided into pupillary block versus non-pupillary block. Pupillary block is where a mid-dilated iris in an already crowded eye makes contact with the lens in a way that impedes aqueous flow through the pupil. This causes a pressure buildup behind the iris, shifting it anteriorly which further closes the angle and creating a closed fluid system with no outflow, thus rapidly increasing IOP.

Chronic angle closure can cause permanent vision loss over time due to a chronically elevated IOP but typically does not cause pain because of the eye’s ability to adapt to the gradual change in IOP over time.

Patient Presentation

In AACG, patients present with severe eye pain, redness, nausea, vomiting, blurred vision, headache, and may complain of seeing halos around lights. Risk factors for AACG include age (older than 50), being Asian, female or far-sighted (hyperopic). The crisis can be triggered by events that cause pupillary dilation, such as darkened movie theaters, stress or certain medications/drugs. Examination will reveal an elevated IOP, a reddened eye with a steamy cornea (corneal edema) and a moderately dilated pupil that is not reactive to light. Again, a slow, steady rise in IOP over weeks to months—such as in chronic angle closure—is painless and asymptomatic until either detected by a clinician or the patient has substantial and often irreversible optic nerve damage and vision loss.

Treatment

AACG warrants an emergent ophthalmology consult. Untreated patients can develop permanent vision loss within hours of symptom onset. Initial treatment is targeted to relieve the acute symptoms and reduce the IOP, which is primarily done by drops and oral medicine. Medical therapy works via suppression of aqueous humor production and includes:

- Oral or topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (acetazolamide, dorzolamide)

- Topical beta-blockers (timolol)

- Topical alpha-2 adrenergic agonists (brimonidine)

Once the pressure is stabilized, surgical intervention can be employed to reduce the risk of future events, such as a laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI). LPI is the more definitive treatment of primary AACG and should be performed 24-48 hours following resolution of an acute attack in order to prevent future attacks. LPI corrects a pupillary block by using a laser to create an opening in the iris, thereby allowing aqueous fluid to bypass the pupil.

Image:

This is a diagram of an open angle where the aqueous freely flows around the pupil from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber and out the trabecular meshwork. On the right is a close angle in pupillary block. This image illustrates several risk factors for AACG, including a thickened lens (which happens with age) and a narrow anterior chamber. The aqueous is blocked by the iris-lens contact, thus causing pressure to increase in the posterior chamber which pushes the iris forward and closes off the angle or trabecular meshwork.

References:

Khazaeni B, Khazaeni L. Glaucoma, Acute Closed Angle. [Updated 2017 Apr 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430857/. Accessed 5/18/2018.

Weinreb RN, Aung T., Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: a review. JAMA. 2014;311:1901–1911.

Faculty Approval by: Griffin Jardine, MD

Footer:

Copyright statement: Copyright Author Name, ©2018. For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: http://morancore.utah.edu/terms-of-use/