Combined Retinal Vein and Artery Occlusion: A Case Series

Home / Retina and Vitreous / Other Retinal Vascular Disease

Title: Combined Retinal Vein and Artery Occlusion: A Case Series

Authors: Hansen Dang, BS; George Sanchez, MD; Brian Solinsky, MD; Akbar Shakoor, MD

Date: 8/12/2024

Keywords/Main Subjects: Retinal occlusion, cilioretinal artery, central retinal vein occlusion

Diagnosis: Combined retinal vein and artery occlusion

Description of Case:

Introduction

Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is the second most common retinal vascular disorder that primarily affects older populations. In rare instances, CRVO can be accompanied by a retinal arterial occlusion leading to a combined retinal vein and arterial occlusion. This is a case series discussing two patients with this entity.

Case 1

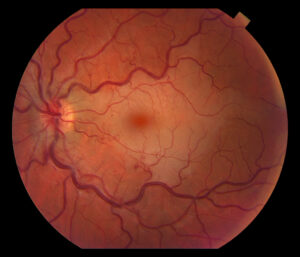

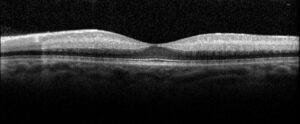

A 28-year-old otherwise healthy female presented with sudden vision loss following a headache that occurred four days prior. She reported loss of central vision with intact peripheral vision of the left eye. Notably, she has a history of migraines associated with blurry vision changes lasting half the day. On exam, visual acuity of the left eye was counting fingers at face distance. Fundus exam of the left eye was remarkable for macular edema, retinal whitening with a cherry red spot, and marked dilation of venules with tortuosity; this was corroborated on fundus imaging (Figure 1). Humphrey visual field demonstrated a central scotoma. Fluorescein angiography was performed, and a diagnosis of combined CRVO and central retinal arterial occlusion (CRAO) of the left eye was made. Additionally, findings on ocular coherence tomography were consistent with a CRAO (Figure 2). She was evaluated by the neurology service. A complete stroke and coagulopathy workup, including computed tomography angiography head/neck, echocardiogram, and all pertinent markers of hypercoagulability, was completed. The workup was unremarkable other than a slightly elevated Factor VIII activity at 234% (normal range: 56-191%). She was discharged home on 81mg aspirin daily. Visual acuity was stable on follow-up.

Case 2

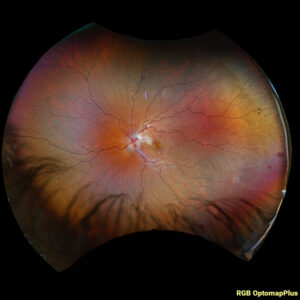

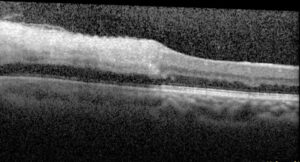

A 30-year-old female with hyperlipidemia presents to the emergency department with intermittent eye pain exacerbated with eye movements and worsening blurry vision in the left eye that started four days ago. She had two similar episodes in the past two weeks, but these episodes self-resolved. On exam, visual acuity in the left eye was 20/20 -1. Additional findings were remarkable for a relative afferent pupillary defect and mild red desaturation. Fundus exam was showed for grade VI optic disc edema, retinal whitening of the nasal macula along with the distribution of the cilioretinal artery, and diffuse venous tortuosity. These findings were also seen on fundus imaging (Figure 3). Virtual visual field showed inferior altitudinal and superior arcuate defects. Fluorescein angiography revealed the diagnosis of CRVO and cilioretinal artery occlusion (CLRAO) (Figure 4). OCT macula findings correlated with the CLRAO (Figure 5). Optic neuritis was originally suspected, but imaging did not reveal optic nerve enhancement. She was evaluated by the neurology service. A complete stroke and coagulopathy workup including computed tomography angiography head/neck, echocardiogram, and all pertinent markers of hypercoagulability, was completed. This was unremarkable, aside from an elevated antinuclear antibody level. The patient was discharged home on 81 mg aspirin daily with outpatient follow-up planned.

Discussion

The two patients presented were both cases of CRVO with retinal artery occlusion, albeit involving different arteries. Both patients were female and younger than the typical age for isolated CRVO patients, which is consistent with prior studies.(1, 2) Additionally, both were relatively healthy, each having only one identifiable clinical risk factor for retinal vein occlusion: migraines in case patient 1 and hyperlipidemia in case patient 2.(3) Coagulopathy panels were performed to rule out known risk factors for combined occlusion in this age group and were mostly unremarkable. Case patient 1 did, however, have elevated factor VIII activity, which has been shown to be a significant risk factor for venous thromboembolism, including CRVO.(4-6) There has been a documented case of a patient with combined CRVO and CRAO with elevated fibrinogen and factor VIII to 560%.(7) Notably, case patient 2 had an unremarkable workup that did not reveal underlying clotting tendency.

Despite their similarities, the two had drastically different visual outcomes, likely due to different arterial involvement. The mechanism of combined venous and arterial occlusions remains unclear, but a common explanation involves a reduction in retinal perfusion pressure.(1) The retina’s venous drainage is handled solely by the central retinal vein whereas the arterial supply is more variable. In the presence of a cilioretinal artery, the retina has two independent arterial sources: the central retinal artery arising from the ophthalmic artery and the cilioretinal artery arising from the posterior ciliary artery. If arterial pressures are greater than venous pressures, blood will flow appropriately, and the retina remains perfused. In the setting of CRVO, retinal venous pressure quickly rises. Therefore, to maintain perfusion, the arterial pressures must rise as well. The central retinal artery has no issues doing so due to its autoregulatory system. In response to decreased ocular perfusion pressure, local vascular dilation occurs in response to local oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions as well as pH level thereby leading to decreased vascular resistance and restoring adequate perfusion of the retina. This autoregulatory system is found in the central retinal artery. However, the cilioretinal artery does not have this luxury and thus is more prone to hypoperfusion. This was likely what happened in case patient 2. She demonstrated a cilioretinal artery occlusion without foveal involvement, resulting in better a visual outcome. For case patient 1, the CRVO likely caused a marked increase in venous pressure that overcame the central retinal artery’s autoregulatory capabilities, causing poor perfusion and larger retinal ischemia owed to the larger distribution of the central retinal artery. Therefore, the case patient had a worse visual outcome and prognosis. This patient, unlike case patient 2, did not have a cilioretinal artery.

Images:

Figure 1. Fundus photo of the left eye of case patient 1 showing retinal whitening with a cherry red macula and dilated tortuous vessels.

Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography macula of the left eye of case patient 1 showing inner retinal thickening, loss of architecture and hyperreflectivity consistent with central retinal artery occlusion.

Figure 3. Fundus photo of the left eye of case patient 2 demonstrating retinal whitening along distribution of cilioretinal artery distribution.

Figure 4. Fluorescein angiography of the left eye of case patient 2 showing no filling in the distribution of the cilioretinal artery.

Figure 5. Optical coherence tomography macula of the left eye of case patient 2 showing inner retinal thickening and hyperreflectivity in the distribution of the cilioretinal artery.

Summary of the Case: Combined retinal vein and arterial occlusion is a rare condition with variable presentations and outcomes, depending on the specific artery and extent of involvement.

References:

- Hayreh SS, Fraterrigo L, Jonas J. Central retinal vein occlusion associated with cilioretinal artery occlusion. Retina 2008;28:581-594.

- Raval V, Nayak S, Saldanha M, Jalali S, Pappuru RR, Narayanan R, Das T. Combined retinal vascular occlusion: Demography, clinical features, visual outcome, systemic co-morbidities, and literature review. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020;68:2136-2142.

- Tilleul J, Glacet-Bernard A, Coscas G, Soubrane G, Souied EH. [Underlying conditions associated with the occurrence of retinal vein occlusion]. J Fr Ophtalmol 2011;34:318-324.

- Glueck CJ, Hutchins RK, Jurantee J, Khan Z, Wang P. Thrombophilia and retinal vascular occlusion. Clin Ophthalmol 2012;6:1377-1384.

- Kraaijenhagen RA, in’t Anker PS, Koopman MM, Reitsma PH, Prins MH, van den Ende A, Buller HR. High plasma concentration of factor VIIIc is a major risk factor for venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2000;83:5-9.

- Kyrle PA, Minar E, Hirschl M, Bialonczyk C, Stain M, Schneider B, Weltermann A, et al. High plasma levels of factor VIII and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2000;343:457-462.

- Chang IB, Lee JH, Kim HW. Combined Central Retinal Vein And Artery Occlusion In A Patient With Elevated Level Of Factor VIII: A Case Report. Int Med Case Rep J 2019;12:309-312.

Faculty Approval by: Dr. Akbar Shakoor, MD

Copyright statement: Copyright Hansen Dang ©2024. For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: http://morancore.utah.edu/terms-of-use/