Prism

Home / Clinical Optics / Geometric Optics

Title: Prism

Authors: Jennifer Nightingale, OD; David Meyer, OD, FAAO

Date: 6/30/22

Keywords/Main Subjects: Prism, Apex, Base, Diplopia, Maddox Rod, Lensometer, Fresnel Prism

Description of Case: This paper outlines the definition of a prism and the types of patients that prisms benefit. It also describes how much prism to prescribe to achieve best possible outcomes. Finally, it describes how to read the prism amount on a manual lensometer and discusses the application of Fresnel prism.

What is a prism?

A prism is a type of lens that changes the location of an image by bending light. This is different from a traditional lens that changes the clarity of an image by converging or diverging light.

An optical prism is made of a clear material such as glass, with refracting surfaces non-parallel to one another. It has both a base and an apex – it is important to keep in mind that the prism bends light toward the base, causing the image to be perceived in the direction of the apex (see Figure 1).

Who can prisms help?

Prisms can improve the quality of life for people with a variety of ocular conditions:

- Ocular deviations

- When a patient’s eyes are misaligned, the images reaching their foveae are different resulting in diplopia. A prism can align the image with the new location of the patient’s fovea, with the goal of eliminating the diplopia. For example, someone with an esotropia, or inward deviation of an eye, can benefit from “base out” prism in their glasses. This would move the image in toward their nose, where their fovea naturally lies.

- Convergence insufficiency

- In this case, patients can benefit from “base in” prism in their reading glasses. This moves the image temporally, which reduces the convergence demand on the ocular system.

- Stroke patients with resulting visual field loss

- It is common for patients with a recent history of stroke to exhibit homonymous hemianopsia, or the loss of one side of their visual field. Strategically placing prism above and below the patient’s line of sight is an option to expand the patient’s horizontal visual field, improving functional mobility.

- Add over +4.00

- Patients with an add over +4.00 require a much closer working distance (for example, a +6.00 add would have a working distance of 16cm). Whether for those with low vision or those with extremely detailed near tasks, this greatly increases the convergence demand. Similar to those with convergence insufficiency mentioned above, these patients can benefit from “base in” prism. A good starting point is to take the add power + 2, and use that much per lens (that same +6.00 add would have 8pd BI per lens, or 16pd BI total); however, trial framing in office is recommended.

How much prism to prescribe

The Maddox rod is a great tool for determining a starting point of how much prism to put into glasses. This, combined with a prism bar, provides a relatively quick way to measure the patient’s subjective deviation. This can be used for either horizontal prism (with the Maddox rod oriented horizontally) or vertical prism (with the Maddox rod oriented vertically).

For example, a horizontal Maddox rod can be placed over the patient’s left eye, while a horizontal prism bar is simultaneously held over the right eye. The bar can be easily shifted between prism amounts until the patient reports the white light and red line are in alignment – this is the subjective deviation.

When it comes to fine-tuning a prism prescription, there is no replacement for trying out prism in-office in a trial frame. In this way, a patient can give you feedback about their visual experience in real time as you trial different amounts of prism. Remember that less is more – you are looking for the least amount of prism that allows the patient to have single and comfortable vision.

For low powered prism trial lenses it can be difficult to determine which direction the base is. A practical tip is to hold it up to a vertical line such as a door frame and see which direction the line is shifted. If the image is shifted to the right, the prism apex is on the right, and the base is on the left.

How to split the prism between the eyes

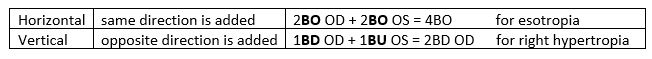

When it comes time to write the prescription, it is standard practice to split the prism equally between the eyes both for patient comfort as well as cosmesis. Horizontal prism varies from vertical prism as follows:

How to read prism on a manual lensometer

- Horizontal

- Mark the interpupillary distance on the lenses

- Center the mark for the right lens on the lens stop

- Record the amount and direction of the crosshair decentration (see Figure 2, right lens, showing 2pd BI).

- Repeat for left lens

- Vertical

- Complete lensometry, measuring the lens powers

- Determine which lens has the greater absolute power in the vertical meridian

- For that lens, center the target within the reticle

- Slide to the other lens and record the amount and direction of vertical decentration, as well as the eye

Fresnel prism

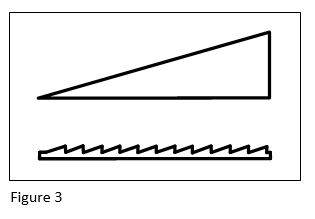

Fresnel prism is a thin sheet of plastic that can be placed on top of a lens (see Figure 3 for conventional vs. Fresnel). While not as cosmetically appealing as grinding the prism into the lens itself, it is a great temporary option. This is beneficial for patients with temporary needs (such as stroke patients) or as a way to trial the prism before committing. It is also possible to incorporate both vertical and horizontal prism in one Fresnel by placing it at an oblique angle calculated by vectors.