39-year-old Male with New-Onset Right Vision Loss

Home / Retina and Vitreous / Focal and Diffuse Choroidal and Retinal Inflammation

Title: 39-year-old male with new-onset right vision loss

Author: Nina Boal, BA

Photographer: James Gilman, CRA, FOPS

Date: September 2017

Images:

Figure 2: MRI of orbits with IV contrast, post-contrast T1 5 mm ring enhancing foci in the right thalamus.

Keywords/Main Subjects: Toxoplasma gondii; Toxoplasma retinitis; HIV; AIDS

Secondary CORE Category: Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis / Ocular Involvement in AIDS (HIV)

Diagnosis: Toxoplasma Retinitis

Discussion of Images:

The fundus photos and MRI are from a 39-year-old male who presented with right sided vision loss over the course of two days. A complete review of systems was positive only for ten-pound weight loss in three months, fatigue, nausea, and bloody stools. The patient immigrated from Guatemala 25 years ago. He endorsed no significant past medical history.

- Vision: OD 20/70; OS 20/20

- Intraocular pressure: normal OU

- Slit lamp examination OU: unremarkable

- Dilated Exam:

- OS unremarkable

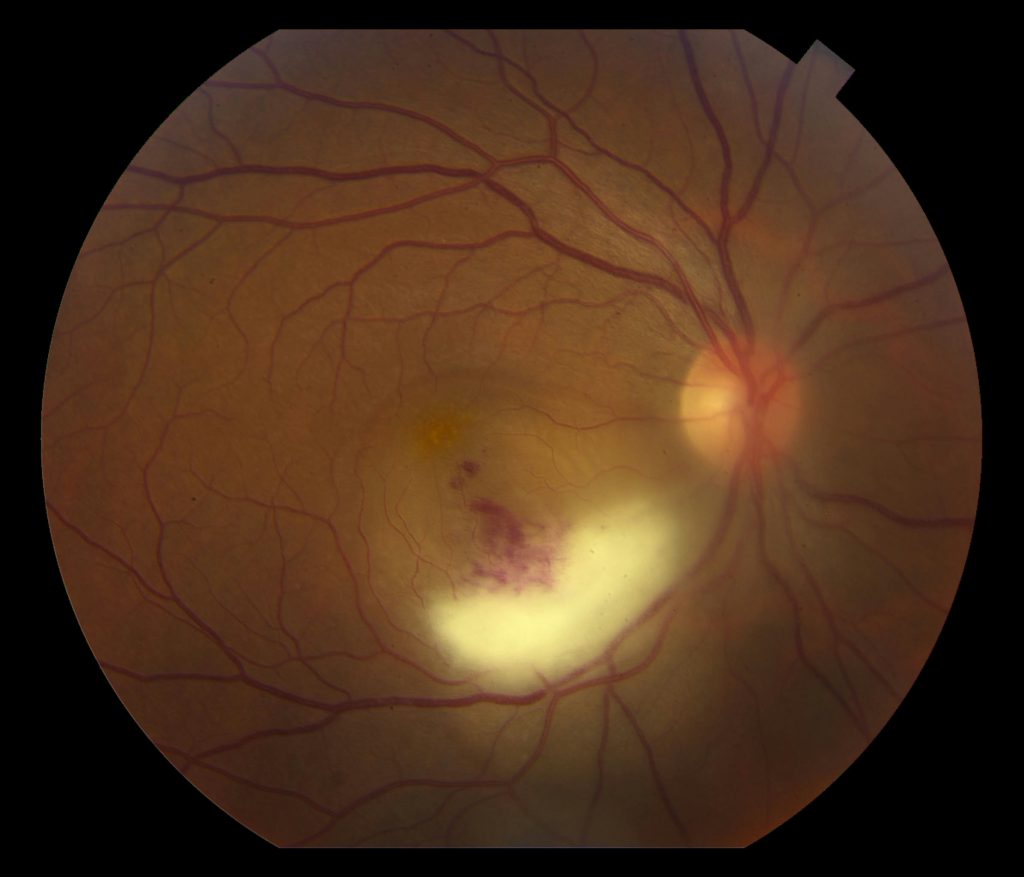

- OD elevated, white sub-retinal lesion in the inferior arcade with overlying vitreous inflammatory haze and hemorrhage was seen in the right eye (Figure 1)

The patient was treated empirically with intravitreous clindamycin and foscarnet, intravenous acyclovir, oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and admitted for work up of endogenous endophthalmitis. Further testing revealed:

- Pancytopenia with a white blood cell count of 2.4

- HIV testing positive; CD4+ T-cell count of 24 cells/mm3; viral load of 1,400,000

- MRI with IV contrast:

- 5 mm ring enhancing foci in the right thalamus (figure 2), in addition to small enhancing lesions in the anterior right frontal lobe and right basal ganglia

- Imaging was read as concerning for neurocystercercosis or toxoplasma

- Vitreous sampling: Toxoplasma gondii PCR positive and CMV negative

The patient was diagnosed with toxoplasma retinitis and AIDS. Other medications started after this admission were emtiracitabine/tenofovir alafenamide and raltegravir. Valgancyclovir and azithromycin were started for CMV and MAC prophylaxis.

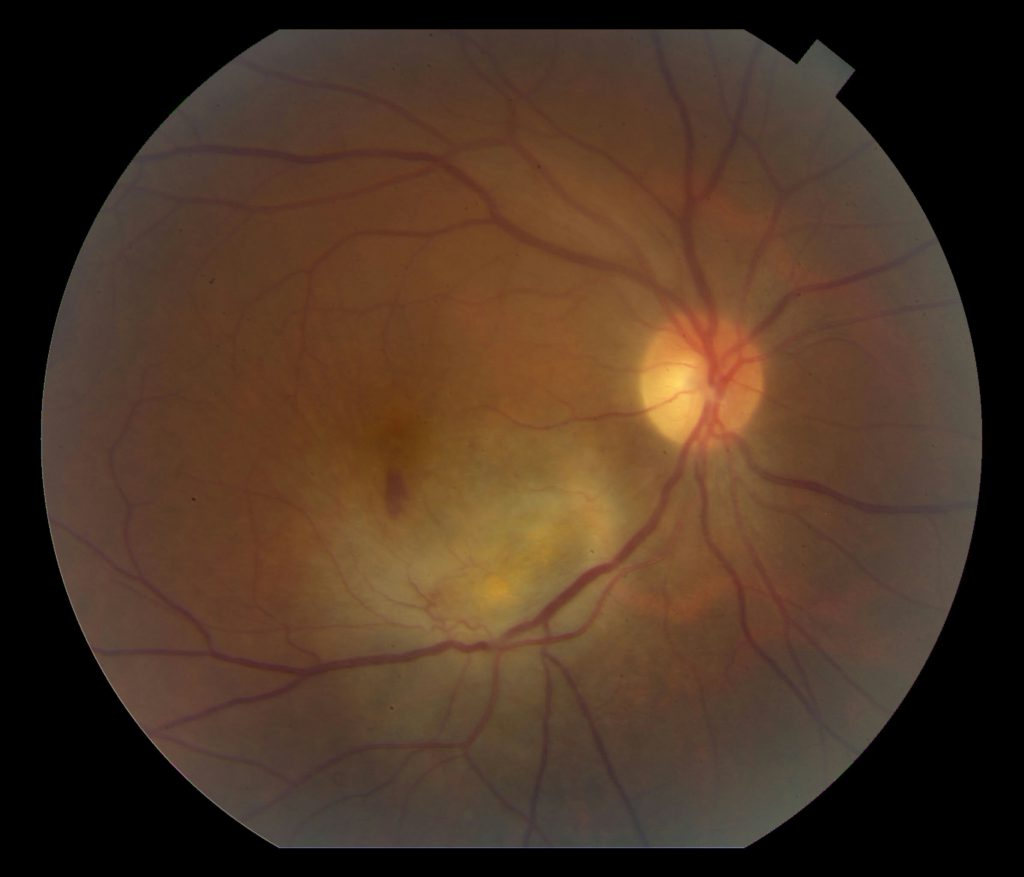

Follow-up appointment 1.5 months after treatment began showed improved vision to 20/40 in the right eye. Dilated fundus exam of the right eye showed improved subretinal fluid and hemorrhages with slightly larger area of retinal whitening along the inferior arcade (Figure 3).

Discussion:

Ocular toxoplasmosis, caused by the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii, is considered to be the most common identifiable cause of infectious posterior uveitis in many parts of the world including northern Europe, North America, and South America. The immune system plays a critical role in susceptibility to infection with toxoplasmosis, and patients are at a particularly high risk when their CD4+ T-cell count is below 200 cells/mm3.

Active ocular toxoplasmosis can appear as focal white fluffy retinal lesions with indistinct borders. Overlying vitreous inflammation is commonly seen, with more severe overlying vitreous inflammation representing more advanced active disease, and classically described as a “headlight in a fog.” Older ocular toxoplasmosis lesions are typically seen as areas of well-circumscribed retinal necrosis, and as the lesion heals, its borders become more defined and hyperpigmented. Ocular toxoplasmosis in an immunocompromised patient typically demonstrates a more fulminant course with multifocal disease in one eye, bilateral eye disease, or extensive areas of necrotizing retinitis that can progress to panophthalmitis and orbital cellulitis. Between 30 and 50 percent of patients with HIV who have ocular toxoplasmosis will have central nervous system involvement.

In healthy patients with peripheral retinal lesions, infection with T. gondii is self-limited and may not require treatment, however treatment is required for patients who are immunocompromised, pregnant, or have vision threatening lesions. There have been three prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials using systemic antibiotics to treat ocular toxoplasmosis. However, two of these studies were conducted almost 40 years ago and they are all considered to be methodologically poor. In the three studies, there was a lack of evidence that antibiotics (short or long term) would prevent vision loss. The “classical triple therapy” remains the combination of oral pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and corticosteroids. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is required for neurotoxoplasmosis, as in this case, and intravitreous clindamycin in combination with dexamethasone was shown to be efficacious in 16 out of 16 patients in a recent study (Zamora YF et al., 2015). Caution may be warranted in the use of steroids for immunocompromised patients.

Format: Images

References:

- Cunningham ET Jr, Margolis TP. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 236–44.

- Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part I: epidemiology and course of disease. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136:973-88.

- Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: a global reassessment. Part II: disease manifestations and management. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 137:1-17.

- Maenz M, Schluter D, Liesenfeld O, Schares G, Gross U, Pleyer U. Ocular toxoplasmosis past, present and new aspects of an old disease. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 2014; 38: 77-106.

- Moshfeghi DM, Dodds EM, Couto CA et al. Diagnostic approaches to severe, atypical toxoplasmosis mimicking acute retinal necrosis. Ophthalmology 2004; 111: 716–25.

- Talabani H, Mergey T, Yera H, Delair E, Brezin AP, Langsley G, Dupouy-Camet J. Factors of occurrence of ocular toxoplasmosis. Parasite 2010; 17: 177-182.

- Zamora YF, Arantes T, Reiz FA, Garcia CR, Saraceno JJ, Belfort JR, Muccioli C. Local treatment of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis with intravitreal clindamycin and dexamethasone. Arg Bras Oftalmol 2015; 78 (4): 216-9.

Faculty Approval by: Griffin Jardine, MD

Copyright: Nina Boal, © For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: URL to copyright information page on Moran CORE

Disclosure (Financial or other): None

Identifier: Moran_CORE_24588