Intermediate Uveitis: case report

Home /Intraocular Inflammation and Uveitis / Noninfections (Autoimmune) Uveitis

Title: Intermediate Uveitis: case report

Author: Christian Curran

Date: 08/13/2021

Keywords/Main Subjects: intermediate uveitis, pars planitis, posterior cyclitis, hyalitis, inflammatory eye disease, noninfectious uveitis, autoimmune disease, autoinflammatory disease, inflammation, snowballs, snowbanks, cystoid macular edema, neovascularization

Diagnosis: Intermediate Uveitis

Intermediate uveitis (IU) primarily consists of inflammation in the anterior vitreous but also includes inflammation of the ciliary body and peripheral retina. The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) working group defined the term to include anterior vitritis, pars planitis, posterior cyclitis, and hyalitis[1]. When an association with systemic disease or infection can be made, the diagnosis of IU lends prognostic significance, as other uveitidies are often less treatable[2-5]. However, even with a full diagnostic workup, a large proportion of IU cases remain idiopathic.

There are numerous causes of intermediate uveitis, and this makes its epidemiology difficult to evaluate. For example, pars planitis uveitis, a subset of intermediate uveitis, has been significantly associated with multiple sclerosis and a female predominance[6]. Yet, no clear gender bias has been demonstrated when all causes of intermediate uveitis are taken into account[7]. Understanding the underlying etiology is therefore important, and the etiologic classification of IU is segmented into infectious and non-infectious causes. Common infectious causes include Borrelia burgdorferi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Toxocara canis, Tropherema whipplei, Treponema pallidum, EBV, HTLV1, HIV, and Chikungunya. Common non-infectious causes include multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, idiopathic optic neuritis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Behcet’s Disease, autoimmune corneal endotheliopathy, sarcoidosis, Vogt-Koyanagi- Harada disease, amyloidosis, and large cell lymphoma[8-13]. Although intermediate uveitis is often idiopathic, as is true with all uveitidies, it is the responsibility of the clinician to rule out all treatable causes of intermediate uveitis in the diagnostic workup.

The pathophysiology of intermediate uveitis is as varied as its underlying disease entities. A genetic predisposition is likely. HLA-DR haplotype has been demonstrated to bear a significant correlation with development of intermediate uveitis, in particular HLA-DR15 which is also associated with multiple sclerosis[14]. Given its association with autoimmune etiologies, as well as elevated intraocular and serum cytokine levels including IL-6, IL-8, CCL5/RANTES and CCL2/MCP-1, an auto-inflammatory process is also likely[15]. Lastly, a prominent T cell contribution is highly likely, given that anti-TNF-alpha treatments are effective in resolving inflammation, and animal models demonstrate that activated T cell transference is sufficient to instigate disease [15-17].

The following patient case is representative of important principles that are common to the presentation and treatment of this disease entity.

Description of Case:

The patient is a 23-year-old female, presenting with no pertinent past medical history, and an ocular history only notable for uveitic glaucoma diagnosed two weeks prior. She complains of blurry vision in both eyes, worse in her right eye than her left eye, and states that this has been happening for years. In the past few months, her vision has worsened noticeably in both eyes. She does not have any family history of eye problems. The patient’s social history demonstrates a recent trip to Vietnam, but is otherwise insignificant, without any history of drug use, sexual activity, or exposure to animals including pets. She denies having pain, fevers, chills, night sweats, skin rashes, difficulty with urination, diarrhea, or constipation. She does have blurring, halos, and a burning sensation in both eyes, as well as some back pain. Her only medications are Durezol and Voltaren eye medications, which she was prescribed when diagnosed with uveitic glaucoma.

Physical exam demonstrated a normal external exam with visual acuity reduced from self-reported 20/20 to 20/80 measured in clinic in both eyes. Pupils were 4 mm and symmetric without evidence of afferent pupillary defect. Tonometry demonstrated pressures of 12 and 13 in the right and left eyes, respectively, and extraocular motions were full. Slit lamp exam was notable only for trace anterior chamber cell in both eyes, and 2+ vitreous cell bilaterally. Fundus exam was notable only for evidence of macular edema bilaterally, with a normal-appearing disc, and no evidence of neovascularization, exudate, or other vascular or retinal pathology.

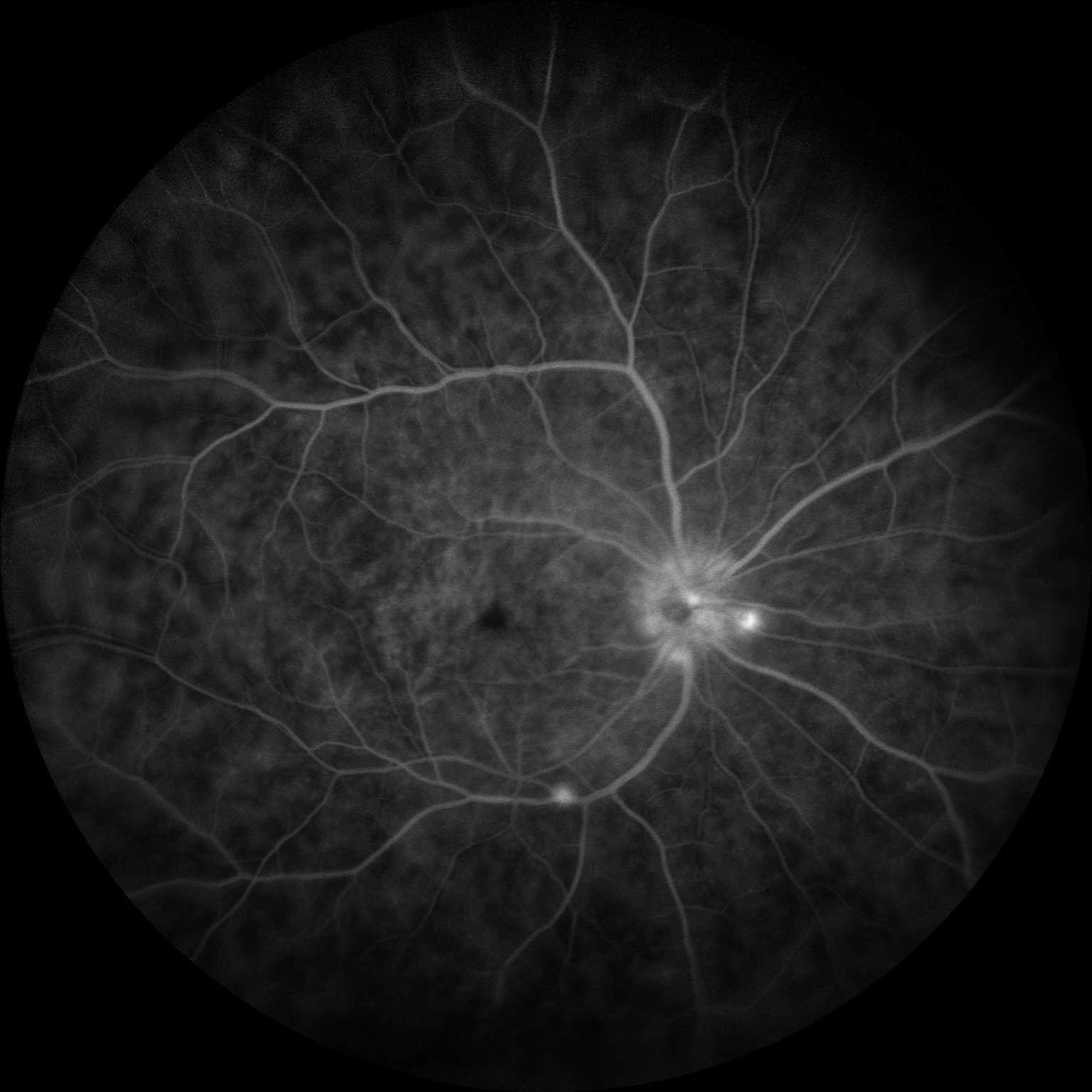

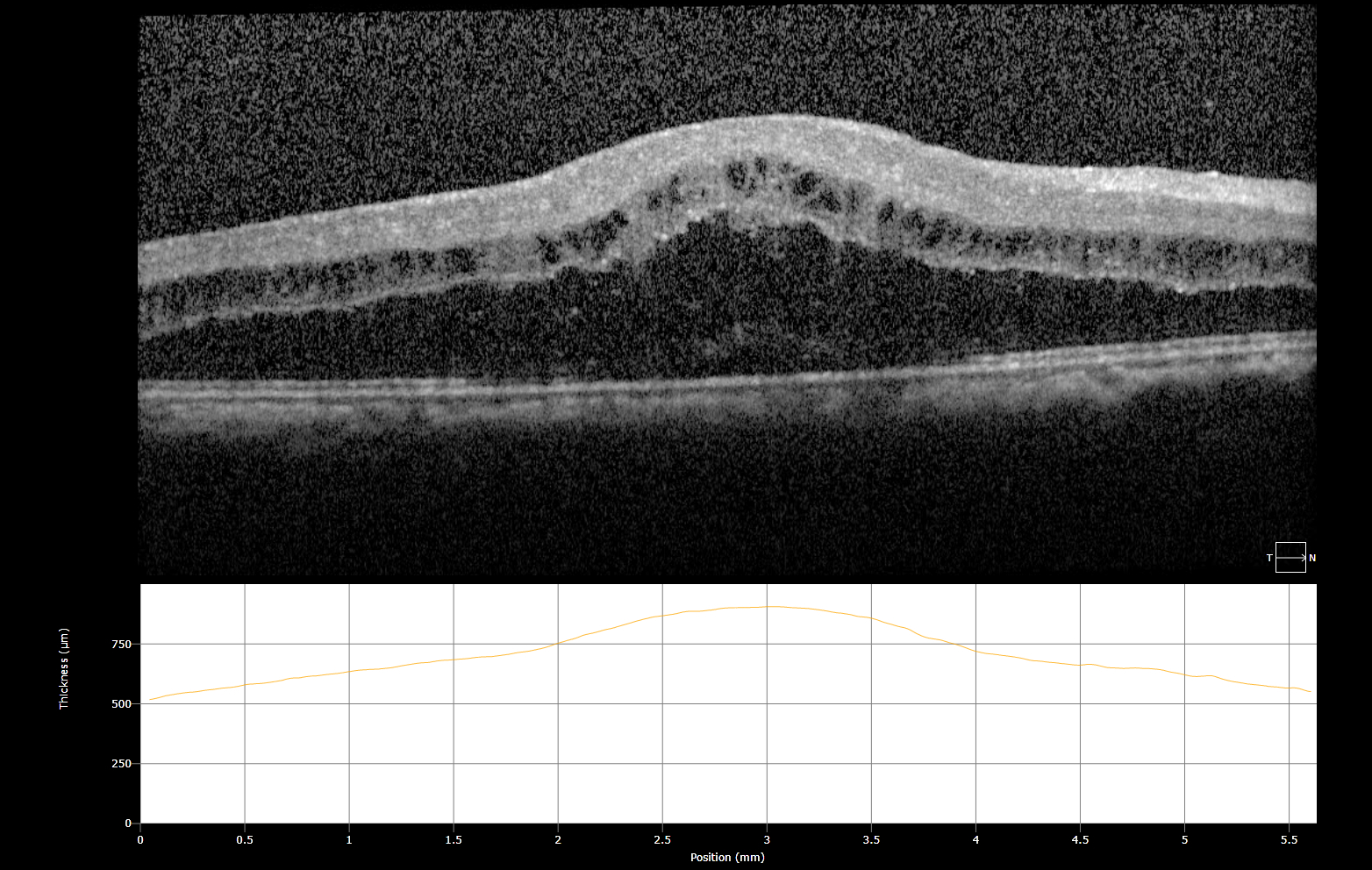

Workup for underlying disease included a broad panel of serum tests: complete metabolic panel (CMP), hepatitis C serology, complete blood count, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS), rapid plasma reagin (RPR), Quantiferon Gold, serum ACE, serum lysozyme, and hepatitis B serology—all of which resulted within normal limits. Imaging was obtained, which included OCT macula and fluorescein angiography of both eyes. Fluorescein angiography demonstrated neovascularization of the disc with capillary leakage (Fig. 1), as well as fern-like leakage of the intraretinal vasculature (Fig. 2). OCT macula demonstrated severe cystoid macular edema bilaterally (Fig. 3).

Imaging:

Figure 1: Early FA demonstrating neovascularization of the disc with capillary leakage

Figure 2: Late FA demonstrating characteristic fern-like leakage of intraretinal vasculature

Figure 3: OCT demonstrating cystoid macular edema (OD)

Figure 4:

OCT demonstrating CME OS

Discussion: Intermediate Uveitis

Intermediate uveitis (IU) is a clinical diagnosis. Criteria include inflammation that is primarily in the anterior vitreous and is restricted to the vitreous, peripheral retina, and ciliary body. When a systemic disease or infection can be identified, the most fitting term is intermediate uveitis. Whereas, when a systemic disease cannot be identified (idiopathic) and the inflammation is restricted to the vitreous, the disease entity is properly identified within a subgroup of intermediate uveitis—pars planitis[1, 18]. Inflammation in IU is documented by four metrics: anterior chamber cells, anterior chamber flare, vitreous cells, and vitreous haze or debris, an ordinal system by which the cells are graded on a scale of 0-4+[1]. While it is an ordinal system and not a nominal one, interobserver agreement within one grade has been shown to be very high for AC cells (kappa range 0.81 to 1.00) and vitreous haze (kappa, 0.75)[3].

IU most commonly presents with blurred vision or floaters [2]. Exam findings may include vitreous “snowballs,” which are white to yellow aggregations of exudate that can be seen floating in the vitreous on exam, and when these snowballs settle along the pars plana to form plaques, they are referred to as “snowbanks”[2, 5]. While these plaques are generally position-dependent and aggregate inferiorly, suspicion of IU warrants a 360-degree exam due to risk of macular hole and retinal detachment.

IU itself is most often benign; however, associated complications can lead to loss of visual acuity, and the underlying cause of the inflammatory disease may result in significant morbidity. The most common causes of vision loss in IU are macular edema and maculopathy, which are worsened by increased disease chronicity and severity[4, 19]. Other causes of vision loss in IU include formation of cataracts and epiretinal membranes, central or peripheral neovascularization, retinal detachment, uveitic glaucoma, and optic nerve disc edema[2, 5, 17]. Visual outcomes are largely dependent on timely resolution of these sequelae and prevention of disease recurrence.

Management of IU, therefore, is focused on calming the inflammatory process, preventing chronicity, and treating sequelae. Periocular injection of corticosteroids such as triamcinolone acetonide with or without systemic corticosteroids is the first line treatment to immediately calm the localized inflammatory process and decrease progression of CME and neovascularization[17, 20]. A long-acting fluocinolone acetonide implant may have benefit in instances of chronic inflammation[21]. In unilateral cases or instances of unilateral recurrence, a subtenon’s triamcinolone injection may be considered[2, 17]. Biologics such as anti-TNF-alpha agents are second-line and used for refractory disease or when corticosteroids are contraindicated[22]. However, they may be considered as first-line treatments in the case of IU associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis or Behçet’s disease[16]. Some evidence suggests that pars plana vitrectomy may help reduce immediate inflammation, resolve CME, and prevent disease recurrence, particularly in pediatric populations[23-25], and that this intervention may be superior to immunomodulatory therapy[26]. PRP lasers and anti-VEGF agents are used for neovascularization of the retina, and other biologic therapies such as anti-IL-6 treatments are under clinical investigation[2, 5, 22, 27]. Preventing recurrence consists of identifying and treating any associated underlying disease etiology, as well as careful consideration of topical steroid use, and tapering of corticosteroids once inflammation has resolved[2, 5]. Treatment of IU sequelae is specific to the given pathology, which is discussed in detail elsewhere in the MoranCORE.

In general, the prognosis for patients presenting with intermediate uveitis is good. Visual outcomes are generally favorable, as long as acute inflammation can be effectively treated and repeated episodes and long-term sequelae can be resolved[4, 5, 28, 29].

Summary of the Case: This case is a common presentation of intermediate uveitis. Intermediate uveitis is characterized by predominant anterior vitritis, accompanied by pars planitis, posterior cyclitis, and/or hyalitis. Common manifestations include blurry vision and floaters. Physical exam findings include vitritis, snowballing, CME, and neovascularization. Common findings on OCT include CME, and FA may demonstrate capillary leakage as well as neovascularization of the peripheral retina and optic disc. First line treatment includes intravitreal or systemic corticosteroids, although numerous treatment modalities are available. Underlying causes include autoinflammatory conditions such as multiple sclerosis, irritable bowel disease, and Behcet’s Disease, as well as infections caused by a variety of organisms including Lyme Disease, syphilis, and HIV.

References:

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working G: Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 2005, 140(3):509-516.

- Babu BM, Rathinam SR: Intermediate uveitis. Indian J Ophthalmol 2010, 58(1):21-27.

- Kempen JH, Ganesh SK, Sangwan VS, Rathinam SR: Interobserver agreement in grading activity and site of inflammation in eyes of patients with uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2008, 146(6):813-818 e811.

- Kempen JH, Van Natta ML, Altaweel MM, Dunn JP, Jabs DA, Lightman SL, Thorne JE, Holbrook JT, Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment Trial Research G: Factors Predicting Visual Acuity Outcome in Intermediate, Posterior, and Panuveitis: The Multicenter Uveitis Steroid Treatment (MUST) Trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2015, 160(6):1133-1141 e1139.

- Winthrop RNS: Uveitis Fundamentals and Clinical Practice, Fourth Edition edn: Mosby Elsevier; 2010.

- Abraham A, Nicholson L, Dick A, Rice C, Atan D: Intermediate uveitis associated with MS: Diagnosis, clinical features, pathogenic mechanisms, and recommendations for management. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2021, 8(1).

- Miserocchi E, Fogliato G, Modorati G, Bandello F: Review on the worldwide epidemiology of uveitis. Eur J Ophthalmol 2013, 23(5):705-717.

- Ness T, Boehringer D, Heinzelmann S: Intermediate uveitis: pattern of etiology, complications, treatment and outcome in a tertiary academic center. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017, 12(1):81.

- Engelhard SB, Patel V, Reddy AK: Intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, and panuveitis in the Mid-Atlantic USA. Clin Ophthalmol 2015, 9:1549-1555.

- Engelhard SB, Bajwa A, Reddy AK: Causes of uveitis in children without juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clin Ophthalmol 2015, 9:1121-1128.

- Barisani-Asenbauer T, Maca SM, Mejdoubi L, Emminger W, Machold K, Auer H: Uveitis- a rare disease often associated with systemic diseases and infections- a systematic review of 2619 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2012, 7:57.

- Elnahry AG, Elnahry GA: Granulomatous Uveitis. In: StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL); 2021.

- Rosenberg AM: Uveitis associated with childhood rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2002, 14(5):542-547.

- Davis JL, Mittal KK, Nussenblatt RB: HLA in intermediate uveitis. Dev Ophthalmol 1992, 23:35-37.

- Valentincic NV, de Groot-Mijnes JD, Kraut A, Korosec P, Hawlina M, Rothova A: Intraocular and serum cytokine profiles in patients with intermediate uveitis. Mol Vis 2011, 17:2003-2010.

- Thomas AS: Biologics for the treatment of noninfectious uveitis: current concepts and emerging therapeutics. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2019, 30(3):138-150.

- Thomas AS, Lin P: Local treatment of infectious and noninfectious intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis: current concepts and emerging therapeutics. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2020, 31(3):174-184.

- Ozdal PC, Berker N, Tugal-Tutkun I: Pars Planitis: Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, Management and Visual Prognosis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2015, 10(4):469-480.

- Sood G, Patel BC: Uveitic Macular Edema. In: StatPearls. edn. Treasure Island (FL); 2021.

- Cunningham ET, Jr., Wender JD: Practical approach to the use of corticosteroids in patients with uveitis. Can J Ophthalmol 2010, 45(4):352-358.

- Jaffe GJ, Lin P, Keenan RT, Ashton P, Skalak C, Stinnett SS: Injectable Fluocinolone Acetonide Long-Acting Implant for Noninfectious Intermediate Uveitis, Posterior Uveitis, and Panuveitis: Two-Year Results. Ophthalmology 2016, 123(9):1940-1948.

- Touhami S, Gueudry J, Leclercq M, Touitou V, Ghembaza A, Errera MH, Saadoun D, Bodaghi B: Perspectives for immunotherapy in noninfectious immune mediated uveitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2021:1-13.

- Figueroa MS, Noval S, Contreras I, Arruabarrena C, Garcia-Perez JL, Sales M, Gil-Cazorla R: [Pars plana vitrectomy as anti-inflammatory therapy for intermediate uveitis in children]. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol 2010, 85(12):390-394.

- Stavrou P, Baltatzis S, Letko E, Samson CM, Christen W, Foster CS: Pars plana vitrectomy in patients with intermediate uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2001, 9(3):141-151.

- Darsova D, Pochop P, Stepankova J, Dotrelova D: Long-term results of pars plana vitrectomy as an anti-inflammatory therapy of pediatric intermediate uveitis resistant to standard medical treatment. Eur J Ophthalmol 2018, 28(1):98-102.

- Quinones K, Choi JY, Yilmaz T, Kafkala C, Letko E, Foster CS: Pars plana vitrectomy versus immunomodulatory therapy for intermediate uveitis: a prospective, randomized pilot study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm 2010, 18(5):411-417.

- Karti O, Ipek SC, Ates Y, Saatci AO: Inflammatory Choroidal Neovascular Membranes in Patients With Noninfectious Uveitis: The Place of Intravitreal Anti-VEGF Therapy. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol 2020, 9(2):118-126.

- Pan J, Kapur M, McCallum R: Noninfectious immune-mediated uveitis and ocular inflammation. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2014, 14(1):409.

- Sood AB, Angeles-Han ST: An Update on Treatment of Pediatric Chronic Non-Infectious Uveitis. Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol 2017, 3(1):1-16.

Faculty Approval by: Akbar Shakoor , MD; Griffin Jardine, MD

Copyright statement: Copyright Christian Curran, ©2021. For further information regarding the rights to this collection, please visit: http://morancore.utah.edu/terms-of-use/