Aniridia

Title: Aniridia

Authors: Judd Cahoon, PhD; Dr. Jeff Pettey, MD

Photographer: James Gillman, CRA, FOPS, Project Administrator Ophthalmic Imaging Date: 7/21/2015

Keywords: Aniridia

Diagnosis/Differential Diagnosis: Aniridia, salzmann’s nodules, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

Description of Case:

42-year-old male with congenital aniridia presents for annual diabetic screen. He has multiple medical comorbidities including type-1 diabetes since the age of 12 and congenital partial agenesis of the corpus callosum. His diabetes is poorly controlled (A1C of 8). The patient states his vision (both near and far) is worsening over the past few years. He states he bumps into things often because he doesn’t see them and this has led to some falls.

Past Ocular History: Cataract surgery in both eyes in 2011

Past Medical and Surgical History: T1DM since age of 12, no other surgeries Medications: Novolin subq daily.

Family History: Mother and father with history of diabetes mellitus, no history of aniridia in family.

Social History: Lives in a house with others who help him make his food. He smokes 8-10 cigarettes a day. No alcohol use or drug use.

Ocular Exam:

• External exam: Normal both eyes (OU)

• Distance visual acuity (Snellen)

o Right eye (OD) 20/200, no improvement with pinhole

o Left eye (OS) 20/250, no improvement with pinhole

• Pupils

o OD: Dark 7mm, light 7 mm, no reaction

o OS: Dark 7mm, light 7mm, no reaction

• Motility: Full OU, nystagmus present in all directions

• Visual Fields

o OD: all peripheral fields decreased

o OS: decreased in inferior nasal and temporal fields

• Tonometry (Applanation)

o OD: 16 mmHg

o OS: 16 mmHg

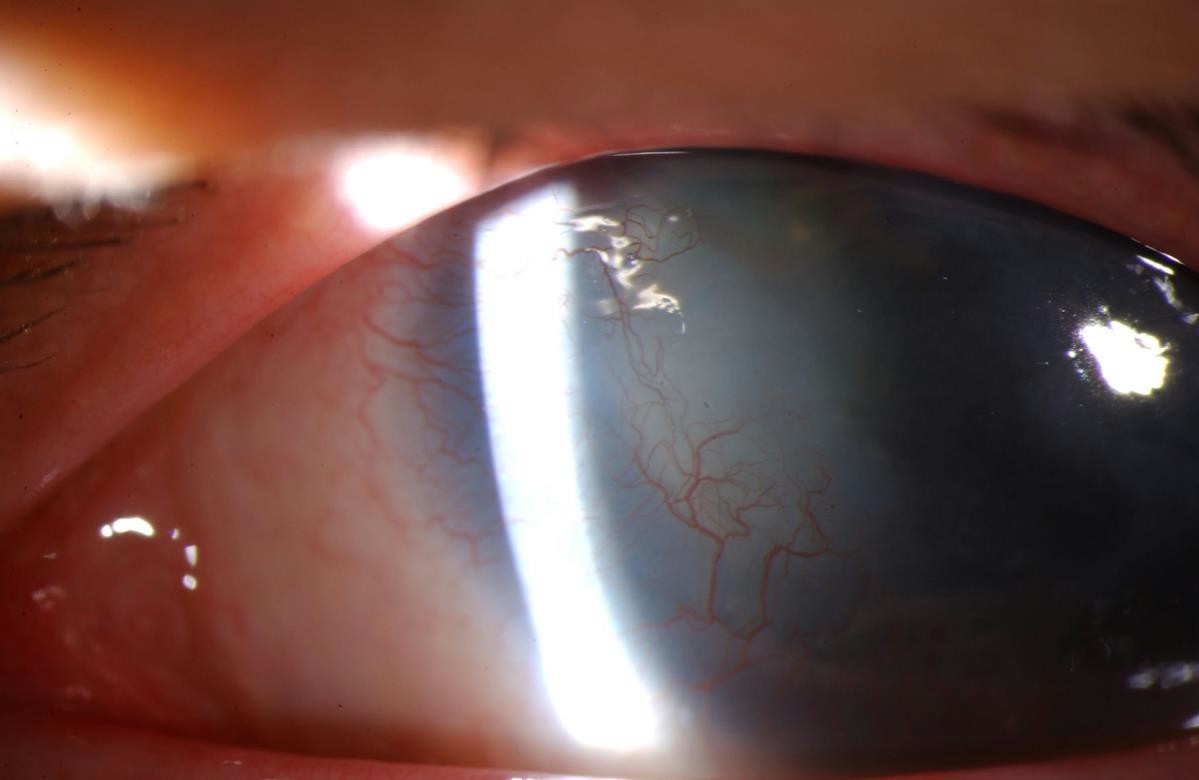

• Anterior Segment exam (Figure 1)

o Lids and lashes: Normal OU

o Conjunctiva and Sclera: white and quiet OU

o Cornea: Inferior circular subepithelial opacity – likely Salzmann’s nodules, OU

o Anterior Chamber: Deep and quiet OU

o Iris: Aniridia OU

o Lens: Posterior chamber intraocular lens, open posterior capsule (OD), PCIOL with 1+ poster capsular opacification (OS)

o Vitreous: normal OU

• Fundus Exam:

o Disc: atrophic area inferior to nerve (OD), normal (OS)

o C/D ratio: 0.6 (OD), 0.65 (OS)

o Macula: normal OU

o Vessels: normal OU

o Periphery: inferonasal circular retinal scar next to optic nerve (OD), normal (OS)

Discussion

Aniridia, or absence of the iris, is estimated to have a prevalence of about 1.8 per 100,000 in the population. It is inherited commonly in an autosomal dominant fashion with complete penetrance but variable expressivity (Familial congenital aniridia), but can also be acquired in both sporadic form (Miller syndrome) or, rarely, in an autosomal recessive fashion (Gillespie Syndrome). Additionally, aniridia can be acquired after trauma. Caused by mutations a gene on chromosome 11p13, PAX6 is involved in regulating transcription in the cornea, lens, ciliary body, and retina, genetic testing can be acquired in patients presenting with aniridia.

Symptoms

Patients with aniridia often present with bilateral absence of the iris, which can be either complete or partial. Caregivers can often notice severe light sensitivity, or photophobia, in the child. Multiple ocular comorbidities are also noted including dry eye, meibomian gland dysfunction, and (as seen in our patient) nystagmus, decreased visual acuity, corneal opacification, aniridia-associated keratopathy, cataracts, and optic nerve hypoplasia. Glaucoma is also of major concern and often develops due to inhibition of aqueous flow by the iris stump blocking the trabecular meshwork. Tonometry, pachymetry, and optic nerve exams, and visual field testing are all useful in the diagnosis of an individual with suspected aniridia. However, aniridia remains a clinical diagnosis that can be supported by genetic testing (for PAX6 mutations). A careful family history is also required to rule out other syndromes.

Clinicians should be suspicious of syndromic sequelae in individuals with sporadic aniridia. WAGR syndrome (Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary abnormalities, and mental retardation) is caused by deletion of the short arm of chromosome 11, which, in addition to PAX6, houses the WT1 gene. Presentation of WAGR syndrome includes characteristic facies (long face, stubby nose, long philtrum) in addition to renal and genital abnormalities. Bardet-Biedl Syndrome is an autosomal recessive disease which, like WAGR syndrome, causes kidney and genitourinary abnormalities, but also includes retinal pigment atrophy, zonular cataracts, and polydactyly.

Treatment

Treatment for aniridia can include colored contact lenses with dark periphery or filter/tinted lenses of photophobia. Importantly, treatment of ocular co-morbidities is paramount.

Preservative free tears may be used to for associated keratopathy and dry eye syndrome. Limbal stem cell transplants with amniotic membranes can prevent corneal pannus and scarring. Regular dilated eye exams are useful to follow optic nerve changes along with pressure checks and visual fields. If genetic testing was not obtained, regular abdominal ultrasounds are useful to screen patients for Wilms tumor.

Images:

Figure 2: Congenital aniridia, left eye. Initial examination shows a large, dark, and dilated pupil that does not react to light.

Figure 3. Aniridia can also present as partial absence of the iris as demonstrated here, with residual iris on the inferior margin. Of note, there is almost always residual iris in all cases of aniridia, but the iris might be so small as only to be visible with careful exam or gonioscopy.

Summary of Case:

Vision usually remains poor in patients with aniridia, around 20/200, thus preserving the vision patients have is of utmost importance. In our patient, the nystagmus and corneal disease were not uncommon findings for someone with aniridia. Neither were his visual field deficits, though his pressure was normal. He had his cataracts removed previously and will be referred to a corneal specialist to follow his Salzmann’s nodules. The patient previously underwent YAG laser for PCO and has some remnant opacifications that could benefit from further treatment. Fortunately, his diabetes has not affected his eyes clinically, yet.

References:

- Goetz K, Vislisel JM, Raecker ME, Goins KM. Congenital Aniridia. March 10, 2015; Available from: http://EyeRounds.org/cases/211-Aniridia.htm

- Hingorani, M., Hanson, I., Van Heyningen, V. Aniridia. European Journal of Human Genetics 2013; 20:1011-1017.

- Kokotas, H. et al: Clinical and molecular aspects of aniridia. Clin Genet. 2010, 77(5):409-20.

- Lee, H., Khan, R. and O’Keefe, M. Aniridia: current pathology and management. Acta Ophthalmologica 2008; 86:708–715.

Copyright statement: Copyright Judd Cahoon, 2016. Please see terms of use page for more information.

UNDER REVIEW